I have no formal education in training in how to debate well. The closest I come to having formal debate experience is years of failure from when I believed Facebook debates (“discussions” is what I used to call them) could actually create healthy discourse. I’ve also watched Jim Carrey’s Liar Liar probably one too many times, but I have a feeling that his portrayal of courtroom antics isn’t exactly true-to-life.

Fortunately, there is one debate concept that I have managed to pick up on over the years that has shaped how I engage in public discourse. That is this: there is a difference between making a negative argument or a positive argument. To put it another way, there is a difference between making a negative case against the position you disagree with and making a positive case for the position you hold. In order to make a complete and persuasive argument, you must be able to articulate both a negative and positive case. Otherwise your argument is incomplete and ineffective.

Unfortunately, I think this is a concept that many Christians need to learn (truth be told, I think the general consensus would be that Western society needs to learn this concept – but that is outside of the scope of this article!). Too often I find that when Christians engage publicly with other people and try to make a case for their views, they only do so by making a negative case against the position they disagree with. I rarely hear persuasive and positive arguments for the Christian faith. Many Christians are good at pointing out what they don’t like about other people’s views and positions; they’re not so good at positively articulating why their view or beliefs are better.

Friends, it is a very bitter tasting flavor of Christianity which can only make a case for itself by tearing down the views of others.

I’ve seen this play out not only when Christians engage non-Christians, but also when Christians engage other believers in areas where they happen to disagree. This sad reality then creates a Church where Christians are unable to engage in healthy disagreement and conversation because we’ve so negatively painted other views and positions. Nobody said we have to agree on every theological issue, but we do need to engage each other with love (John 17:20-26, Galatians 5:6). That means we need to be able to emphasize positive arguments for our positions, rather than focusing on what we think is wrong with other views.

Here are a few examples of the kinds of negative argument’s I’ve seen come from Christians the last few years:

- Christianity is right because your religion is wrong. This point is really a bucket for all kinds of poor arguments for Christianity I have heard. One example I have frequently heard is, “Christianity is true because prophets from all the other world religions are still dead!” Ok, true. But what is it about Jesus’ resurrection that actually makes a case for why I can and should trust him? What positive impact does Jesus being raised from the dead actually have on my life? Why does it matter?

I’ve also heard arguments such as, “Christianity is true because other worldviews don’t make proper sense of the world.” Maybe so. But how does Christianity make better sense out of the world?

I was recently sitting in a skeptics meeting where a popular Christian evangelist was brought up. Every single one of the skeptics I was meeting with an aversion to this evangelist because of what he represented to them: someone who couldn’t make a good case for Christianity and instead jumped around from subject to subject trying to tear apart the atheist position. Is this the kind of evangelism we want to be known for?

- Your church has poor worship because it’s not regulative enough. This is something I hear often in Reformed circles. We’re really good at critiquing seeker-sensitive mega-church worship, but we’re really terrible at articulating why the Regulative Principle of worship is both better and healthier in the life of the church.

- Your view of spiritual gifts is wrong because it’s dangerous. I’ve heard this come from either side of the continuationist/cessationist debate. Cessationists will often charge continuationists with dangerous manipulation and expressions of the sign gifts in churches. Continuationists accuse cessationists of “quenching the Spirit,” or imposing some kind of authoritarian rule from the pulpit. This only leads to stereotyping and misrepresentation of our brothers and sisters in Christ. We need to be able to lovingly and clearly articulate why our views are both more biblical and healthier for the life of God’s people today before we jump to negative conclusions about someone else’s views.

- The way you read the Bible is wrong and unhealthy. This argument can come in many forms. I’ve heard people attack the method of Bible reading (“You’re reading is too individualistic” or, “You’re not Christ-centered enough”, etc.). I’ve also heard attacks on the very concept of individual Bible reading (“Christians can’t interpret the Bible on their own” or, “Bible reading should only be done in community”, etc.). There may be truth in these criticisms. But you need to be able to make a positive case for how you want me to read the Bible rather than just making a case against how I do it.

These are just a selection of the kinds of things I commonly hear in Christian circles. Friends, if we want to see our non-Christian friends persuaded to the glories of our faith, then we need to be able to make a positive case for what we believe. And we need to start by being able to make a positive case for what we believe with each other. If we’re unable to do this together as the family of God, how will we ever do it well with those who are looking in from the outside?

In the beginning of Tim Keller’s book Making Sense of God, he longs for a culture where people are able to engage with each other in healthy and respectful discourse. He longs for the kind of place where “people who deeply differ nonetheless listen long and carefully before speaking. There people would avoid all strawmen and treat each other’s objections and doubts with respect and seriousness. They would stretch to understand the other side so well that their opponents could say, ‘you represent my position in a better and more compelling way that I can myself.’”

I too long for this kind of healthy discourse. One of the ways we’ll get there is if we can learn how to emphasize positive arguments before we use negative arguments in our discourse and conversation. Let’s grow in this together.

How are we today as the Church meant to read the creation account as told in Genesis 1 and 2? Many Evangelical leaders today paint the picture that the only faithful interpretations of these chapters are an explicitly “literal” one, meaning that Christians must believe in a young earth, creationist science, etc. One only needs to briefly read and listen to the likes of Ken Ham and Ray Comfort to see how their teachings have permeated into many modern churches and pastors. Such leaders would have us believe this view of creation and our origins is not only the only choice a Christian has, but is also the historic view of the church.

But is this really the case? Is a literal 6-day young-earth reading of creation really the only way to read the text? Indeed, is it even the most historically and Biblically faithful? Many proponents of the Creation movement today would have us believe so. However, when we actually turn to the pages of church history itself, we actually find something quite different. Through a brief study of some of the giants of church history (from antiquity to today) is that a literal creationist reading has not always been the way the church has read the text. I want to briefly consider the works of 6 figures from church history, who I have selected because of their influence as well as their clarity on the subject at hand.

St. Augustine

One of the great giants of the historic Christian faith, St. Augustine, has some very interesting things to say to us in regards to our interpretations of Genesis. In his work On Genesis: A Refutation of the Manichees he deals intently with an explicitly literal interpretation of the opening chapters of Genesis. Carrying on in what could be regarded as an apologetical and polemical tone, he largely proves the impossibility of taking everything in Genesis as literally as possible. He also has quite a strong word towards those who would forsake reason and logic in our observations of the modern world in order to hold on rigidly to such a literal reading. In many ways, this makes Augustine’s comments as relevant today as it did 1600 years ago. Towards the end of his work, he has this to say for such people who hold to rigid readings of Genesis:

There is knowledge to be had, after all, about the earth, about the sky, about the other elements of this world, about the movements and revolutions or even the magnitude and distances of the constellations, about the predictable eclipses of moon and sun, about the cycles of years and seasons, about the natures of animals, fruits, stones and everything else of this kind. And it frequently happens that even non-Christians will have knowledge of this sort in a way that they can substantiate with scientific arguments or experiments. Now it is quite disgraceful and disastrous, something to be on one’s guard against at all costs, that they should ever hear Christians spouting what they claim our Christian literature has to say on these topics, and talking such nonsense that they can scarcely contain their laughter when they see them to be “toto caelo,” as the saying goes, wide of the mark. And what is so vexing is not that misguided people should be laughed at, as that our authors should be assumed by outsiders to have held such views and, to the great detriment of those about whose salvation we are so concerned, should be written off and consigned to the waste paper basket as so many ignoramuses.

Whenever, you see, they catch out some members of the Christian community making mistakes on a subject which they know inside out, and Christians defending their hollow opinions on the authority of our books, on what grounds are they going to trust those books on the resurrection of the dead and the hope of eternal life and the kingdom of heaven, when they suppose they include any number of mistakes and fallacies on matters which they themselves have been able to master either by experiment or by the surest of calculations? It is impossible to say what trouble and grief such rash, self-assured know-alls cause the more cautious and experienced brothers and sisters.[i]

This is a strong word from one of the great church Fathers! What is he getting at? In summary, he is arguing for how dangerous it is for Christians to argue for things from Scripture that simply do not exist, for the sake of their own pride and ignorance. This is so dangerous because, in effect, it is hardening the non-Christians who are experts in the physical observation of this world to the gospel of salvation. What is interesting is how he appears to value the observations of the physical world that come from non-Christians. Augustine does not have a militant view of outside scientific observation, but instead he welcomes it. This comes from Augustine’s confidence in God’s Word and his ability not to force it to say something that it does not say. We would be wise to heed his advice in this area.

Thomas Aquinas

Edward Grant is the Distinguished Professor of History and Philosophy of Science at Indiana University. In his essay Science and Theology in the Middle Ages, he outlines Thomas Aquinas’ view on creation and Biblical interpretation. He quotes Aquinas, who followed in Augustine in his though, as saying the following: “First, the truth of Scripture must be held inviolable. Secondly, when there are different ways of explaining a Scriptural text, no particular explanation should be held so rigidly that, if convincing arguments show it to be false, anyone dare to insist that it still is the definitive sense of the text. Otherwise unbelievers will scorn Sacred Scripture, and the way to faith will be closed to them.”

Grant goes on to explain Aquinas further:

These two vital points constituted the basic medieval guidelines for the application of a continually changing body of scientific theory and observational data to the interpretation of physical phenomena described in the Bible, especially the creation account. The scriptural text must be assumed true. When God “made a firmament, and divided the waters that were under the firmament, from those that were above the firmament,” one could not doubt that waters of some kind must be above the firmament. The nature of that firmament and of the waters above it were, however, inevitably dependent on interpretations that were usually derived from contemporary science. It is here that Augustine and Aquinas cautioned against a rigid adherence to any one interpretation lest it be shown subsequently untenable and thus prove detrimental to the faith.[ii]

What is striking about both Augustine and Aquinas’ view is how they perceive rigid and literal interpretations of Scripture – contrary to scientific evidence – as being so harmful to our evangelism and witness. I wonder if the efforts of outspoken creationists today have similarly hurt our witness in the scientific community today because of their perceived hostility to the efforts of modern science?

John Calvin

Another giant of church history, John Calvin, reveals to us a very similar attitude. During the time of his writing of his commentary on Genesis, it appears that one of the biggest scientific discoveries of his day was that one of the moon’s of Saturn was far superior in size and brightness than that of Earth’s moon. Such a finding seemed to call into question the two lights the God placed into the sky in Genesis 1:16. Writing on this passage, Calvin says this:

Here lies the difference; Moses wrote in a popular style things which, without instruction, all ordinary persons, endued with common sense, are able to understand; but astronomers investigate with great labour whatever the sagacity of the human mind can comprehend. Nevertheless, this study is not to be reprobated, nor this science to be condemned, because some frantic persons are wont boldly to reject whatever is unknown to them. For astronomy is not only pleasant, but also very useful to be known: it cannot be denied that this art unfolds the admirable wisdom of God…Had he (Moses) spoken of things generally unknown, the uneducated might have pleaded excuse that such subjects were beyond their capacity…Moses, therefore, rather adapts his discourse to common usage.[iii]

For Calvin, as we can see, the language of Genesis is in the language of “common usage.” It is no problem for Calvin that science – in this case, astronomy – tells us things that appear to not be in the Bible. There is no discrepancy here. As a matter of fact, the very use of science should lead us to praise. Calvin concludes this passage by saying that those who do not worship God on account of their scientific findings “are convicted by its use of perverse ingratitude unless they acknowledge the beneficence of God.” The true tragedy then is not that science tells us things that the Bible does not, but instead that scientists could gather such great information about the creation that does not lead them to praise its Creator.

B.B. Warfield

Another figure of church history who provides us great insight into an orthodox, historic Biblical interpretation of creation and Genesis is the great Princeton theologian B.B. Warfield. Warfield is often regarded as one of the great champions of Biblical inerrancy and inspiration, yet he referred to himself as an “evolutionist of the purest stripe.” Much of his writing of course was coming during the time when Darwinian Evolution was first exploding on to the scene. In the January 1911 edition of The Princeton Review, Warfield wrote an article called “On the Antiquity and the Unity of the Human Race.” In this article, he wrote: “The question of the antiquity of man has of itself no theological significance. It is to theology, as such, a matter of entire indifference how long man has existed on earth.” [iv] What is of theological significance to Warfield then was that as fallen humans we find our unity in Adam, but as regenerate Christians we find our unity in a new federal head, Jesus Christ. Warfield saw no conflict in this doctrine with that of the age of the earth or the origins of humanity.

Mark Noll, writing for BioLogos, summarizes Warfield’s view of evolutionary theory when he writes, “[Warfield] devoted much effort in his later career to indicating how a conservative view of the Bible could accommodate some, or almost all, of contemporary evolutionary theory.”[v] If a reconciliation between scientific theory and Biblical inspiration and authority was of no issue for a giant like B.B. Warfield, then we should find no trouble ourselves in our attempts at reconciling the two.

Tim Keller

In his fantastic article from the BioLogos website entitled Creation, Evolution and Christian Laypeople, Keller argues for a non-literal and potential evolutionary reading of Genesis 1 and 2. He does so by arguing that these chapters fit into a potential genre called “exalted prose narrative.”[vi] His argument does not stem from trying to fit science into the Bible, but instead comes from “trying to be true to the text, listening as carefully as we can to the meaning of the inspired author.”[vii] What is important for Keller, and he argues should be for us today, is how we view the historicity of Adam. The thrust of his argument is what it means to be “in” a covenantal relationship with someone as our federal head. Those of us who have placed our faith in Christ are united to him as our federal representative. Similarly, those of us who are not in Christ are explained in the Bible to still be “in Adam.” Losing the historicity of Adam begins to have serious problems for our understanding of the Bible (including such passages as Romans 5 and 1 Corinthians 15).

Michael Horton

In his large systematic work The Christian Faith, he argues for an understanding of Genesis 1 and 2 that defies modern creationist movements. Horton understands the creation account as a preamble to a covenant treaty between God and his people. He writes: “The opening chapters of Genesis, therefore, are not intended as an independent account of origins but as the preamble and historical prologue to the treaty between Yahweh and his covenant people. The appropriate response is doxology.”[viii] He goes on to quote the Psalmist who writes:

Know that the Lord, he is God!

It is he who made us, and we are his;

we are his people, and the sheep of his pasture.

Enter his gates with thanksgiving,

and his courts with praise!

Give thanks to him; bless his name! (Psalm 100:3-4)

Horton continues his thoughts on Genesis in the next chapter of his book when he writes:

The point of these two chapters (Genesis 1 and 2) is to establish the historical prologue for God’s covenant with humanity in Adam, leading through the fall and moral chaos of Cain to the godly line of Seth that leads to the patriarchs. If these chapters are not intended as a scientific report, it is just as true that they are not mythological. Rather, they are part of a polemic of “Yahweh versus the Idols” that forms the historical prologue for God’s covenant with Israel. Meredith Kline observes that “these chapters pillage the pagan cosmogonic myth – the slaying of the dragon by the hero-god, followed by celebration of his glory in a royal residence built as a sequel to his victory.” As usual, God is not borrowing from but subversively renarrating the pagan myths, exploiting their symbols for his own revelation of actual historical events.[ix]

Of ultimate importance for Horton then, as it should be for us, is that Yahweh is seen to be Lord over man and creation.

**

My goal in sharing these six examples from the pages of church history is not to influence anyone on a particular reading of Genesis. My goal instead is to show an alternative view of how Christians view Genesis 1 and 2 that is often not shown to us by the loudest voices in the debate or in popular media today. I hope this will allow all of us to see, no matter where we fall in this conversation, that there is great freedom and room for charity in how we interpret and read these passages in the Bible. May our conversations within the church reflect such charity and freedom as we partner together in sharing the gospel and showing the world how science and Christianity are not at all at odds with one another.

[i] Augustine, Works of Saint Augustine, trans. Edmund Hill, vol. 13, On Genesis: On Genesis: a Refutation of the Manichees, Unfinished Literal Commentary On Genesis, the Literal Meaning of Genesis (Hyde Park, NY: New City Press, ©2002), 186-87.

[ii] Lindberg and Numbers, God and Nature. Edward Grant, “Science and Theology in the Middle Ages,” pp. 63-64.

[iii] John Calvin, Calvin’s Commentaries, Volume 1: Genesis (Grand Rapids: Baker), 2005, pp. 86-87 (commentary on Genesis 1:16).

[iv] B.B Warfield, “On the Antiquity and Unity of the Human Race,” The Princeton Theological Review 9 (January 1911): 1.

[v] Mark Noll, “Evangelicals, Creation and Scripture,” BioLogos (November 2009): 9, accessed July 30, 2015, http://biologos.org/uploads/projects/Noll_scholarly_essay.pdf.

[vi] Tim Keller, “Creation, Evolution and Christian Laypeople,” BioLogos (November 2009): 4, accessed July 30, 2015, http://biologos.org/uploads/projects/Keller_white_paper.pdf.

[vii] Ibid., 5

[viii] Michael Scott Horton, The Christian Faith: A Systematic Theology for Pilgrims On the Way (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan, ©2011), pp. 337.

[ix] Ibid., 382.

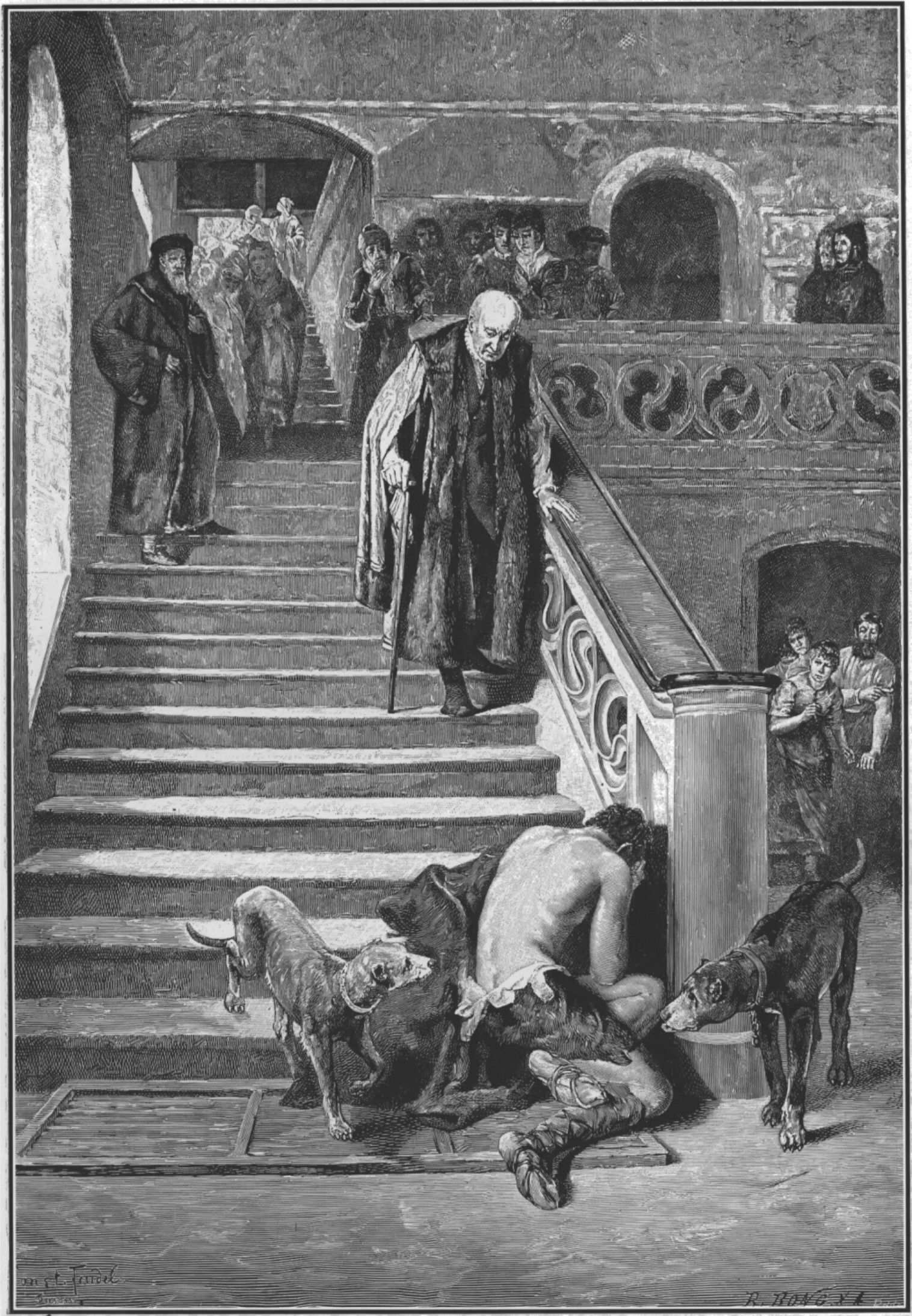

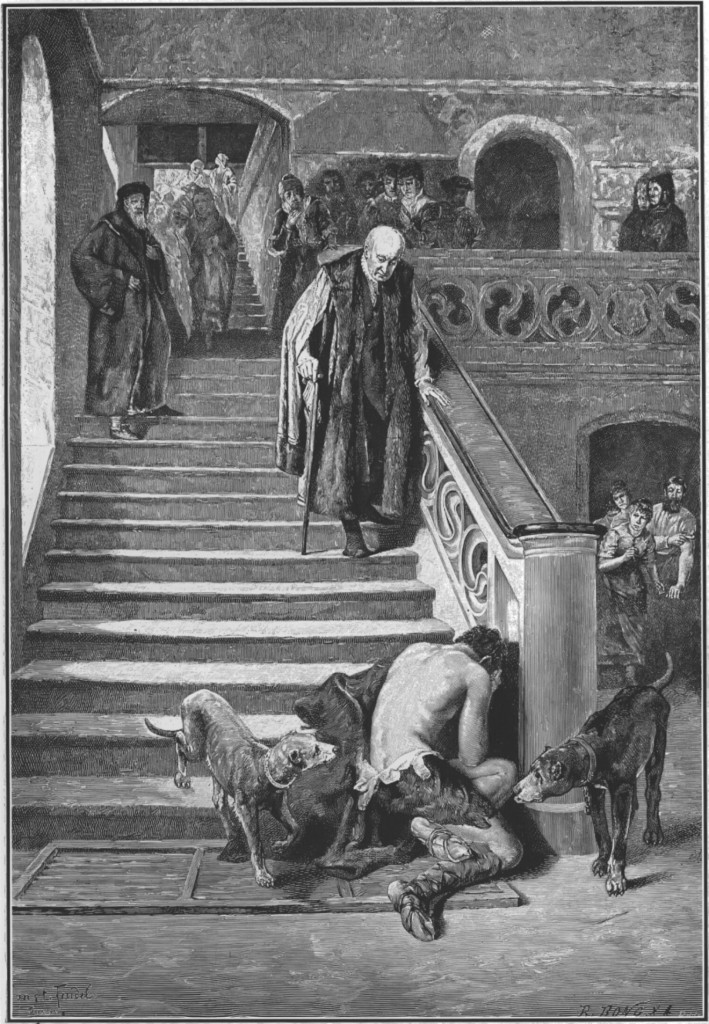

I recently gave one of the most shaping books for my Christian walk – Tim Keller’s The Prodigal God – to my father for his birthday. This book is a short but powerful exposition of the Parable of the Two Brothers from Luke 15:11-32. As I was flipping through the pages and remembering how fond I was of this book, I was struck by one paragraph that I came across at the end of the first chapter. When comparing the difference between the disobedient younger brother and the moralistic, in-it-for-himself elder brother, author Tim Keller writes this:

“Jesus’ teaching consistently attracted the irreligious while offending the Bible-believing, religious people of his day. However, in the main, our churches today do not have this effect…That can only mean one thing. If the preaching of our ministers and the practice of our parishioners do not have the same effect on people that Jesus had, then we must not be declaring the same message that Jesus did. If our churches aren’t appealing to younger brothers, they must be more full of elder brothers than we’d like to think.” (Keller, 15-16)

The climate of the Western Church over the last two centuries has tried two great experiments. The first is the desire to make everything relevant in the church. Exegete and preach the Word, sure, but exegeting and preaching the culture instead is what attracts people, right? On paper, these dear brothers and sisters would still hold to an orthodox Christian faith, but their practice looks much different. A watered-down gospel is preached which lacks the conviction of sin and the grace of our Savior, all-the-while flooding congregants with bright lights and showering them with comfort.

The second experiment has been to reject traditional Christian teachings. If the “dogmatic” authority of the Bible is rejected, if the traditional ethical teachings of Jesus are ignored, if the historic creeds and confessions of the Church are disregarded, then we offer people to come to Christ and stay as they are. If we make Christianity easier for people – so they say – then more people will be attracted to Christ. Yet, these mainline churches are dying just as fast, if not faster, as the first group. There is no gospel-driven power to change in this proclamation. What is sold in these churches is no different than what the world is selling – except the world sells it for much cheaper.

And what is the result of such experimentation? I think author and scholar David Wells puts it best:

“Today, in the evangelical church, there are apparently many who have made decisions for Christ, who claim to be reborn, but who give little evidence of their claimed relationship to Christ. Something is seriously amiss if, as George Barna has reported, only 9 percent of those claiming rebirth have even a minimal knowledge of the Bible, if there are no discernible differences in how they live as compared with secularists, and if the born-again are dropping out of church attendance in droves. If these numbers are anywhere close to being accurate, then the gospel has become a stand-alone thing, and many who say they have embraced it have never entered the Christian life to which it was supposed to be the entry point.” (David F. Wells, God in the Whirlwind: How the Holy-Love of God Reorients Our World, 158)

This dilemma is one area where the teachings and emphasis of the saints of our past can greatly correct and aid us. Orthodox Christianity has always emphasized three important aspects to a saving faith, which come from the earthly ministry of Jesus Christ given to us through his Word:

- Knowledge: We need to know rightly who Christ is, that he alone has the power to save (John 14:6). We need to know and understand that he alone takes away the sin of the world (John 1:29), that he alone is the eternal begotten Son of the Father sent into the world to save sinners (Isaiah 49:6, John 1:1, Mark 2:17, Mark 10:45). If we say we believe in Jesus but do not understand rightly who he is, that is not faith; it’s idolatry.

- Conviction: It is necessary that we be convicted of our sin. We must understand that faith and repentance go hand in hand (Matthew 4:17). We as sinners must know rightly that we are indeed sinners and where that places us before a Holy God. We must be convicted that Christ knows what to do with our sin when we come to him (John 6:68).

- Trust: Every fiber of our being must places its trust in the grace of Christ and not in our own moralism (John 1:17, Luke 24:47). We must transfer the trust from ourselves and our efforts to earn anything to the once-and-for-all work of the blood-stained Savior.

Both the elder brother and the younger brother knew who their father was (Luke 15:12). Yet, it was the prodigal younger brother who was convicted (Luke 15:17-19) and then trusted (Luke 15:20-24) in his father, which led to the great feast at the prodigals homecoming. The elder brother was never convicted of his dependance on his father and therefore never trusted him, and it is for this reason he remained outside of the great banquet. Despite his good works and high sense of morals, the elder brother never came in to the feast. If we want to see more prodigals come home and more moralistic church attenders come to the banquet, then we must present and live out a holistic gospel.

Church, let us press in to be faithful to the God who has called us home to the banquet feast.

Many of you know that I recently got married to an amazing and beautiful woman. It has been about a month now, and while not without our own struggles, I thank God every day for this gift of marriage and the gift of having a bride.

I also continually thank God for the grace he had towards us in our dating relationship. While certainly vulnerable to the temptations and lusts of giving into sexual desires, by God’s grace and mercy we remained pure during our dating and engagement relationship. Admittedly, there came a time when we realized even kissing led to too much temptation, and God gave us the wisdom to realize we just needed to stop altogether.

You might be wondering why I would open a blog post with these details. Well, I share this for a couple reasons. One, to be transparent about the fact that even though we were able to remain pure, we were completely aware of the temptations and desires of our flesh. Two, as an example that remaining pure outside of marriage is entirely possible. This leads me into the subject of today’s post.

Sexual sin is pervasive and has completely infiltrated the Church today. It is rampant and it is everywhere.

Before I continue, a clarification needs to be made. When I speak of rampant sexual sin, I am not speaking of the Christian who is genuinely fighting their struggles with pornography and lust. Our daily struggles with sin is something that continues so long as we are on this side of glory. What I am instead speaking of here is the apathy, laziness and general approval of sexual sin that exists in the Church.

The Western culture has reached a place in its progression through time where complete and total freedom in regards to sexuality is one of the fundamental pillars of society. I’d spend time citing examples to prove my point, but just turn to any major news network or prime-time television show and it will make the point for me.

In contrast to the culture, the Church should embody a Biblical and Godly view of sexuality and marriage. What has instead happened has been a remarkable change in what it means to follow God’s Word in this area. People like the idea of Christianity and having a Savior for their sins, but they do not like the idea of having to submit in all areas of their lives. The recent book by the Barna Research Group entitled You Lost Me puts it this way:

“…many perceive the church and the faith to be repressive. One-fourth of young adults with a Christian background said they do not want to follow all the church’s rules (25 percent). One-fifth described wanting more freedom in life and not finding it in church (21 percent). One-sixth indicated they have made mistakes and feel judged in church because of them (17 percent). And one-eighth said they feel as if they have to live a “double life” between their faith and their real life (12 percent).“

In a culture where sexual freedom is an ideal to strive for, the Church buckles under pressure. Instead of standing for what the Bible speaks on sexuality, sexual freedom is a respectable part of Church culture. Cohabitation, per-marital sex, pornography, adultery, and open relationships have become a norm in many Church settings.

It should be no surprise to us then when Church attendance diminishes, passion for evangelism and outreach ceases, and churches altogether die out. Any brief study of the Bible will show us that in the majority of cases where sin is listed, fighting sexual sin is of utmost importance. Let’s take a look at a few verses:

For this is the will of God, your sanctification: that you abstain from sexual immorality; – 1 Thess. 4:3

Now the works of the flesh are evident: sexual immorality, impurity, sensuality – Gal. 5:19

Flee from sexual immorality. Every other sin a person commits is outside the body, but the sexually immoral person sins against his own body. Or do you not know that your body is a temple of the Holy Spirit within you, whom you have from God? You are not your own, for you were bought with a price. So glorify God in your body. –1 Co 6:18–20.

Any number of verses could continue to be cited in regards to sexual sin. Have you ever pondered why sexual sin is almost always mentioned first in lists of sins, and seems to generally carry more of a weight than sins of other “categories?”

It is for this reason: sexual sin weakens our conscious and clouds our thoughts in ways that most other sins don’t. Whenever sexual sin is present, we grow apathetic in drawing near to Christ because we don’t want him to overcome our weaknesses. We then grow distant and feel ashamed in our lack of passion for God. Finally, we end up distancing ourselves from other Christians because they don’t want them to know about our sin. Fear, guilt, resentment and anger can only result from apathy towards sexual sin. Therefore, we can expect that where apathy towards sexual sin abounds, faithfulness, conversions and a zeal for God will decrease.

To further the problem of killing our own zeal and passion for Jesus, when we give in to sexual sin as if it is acceptable for the Christian life, it entirely kills our witness to the unbeliever. Nobody wants to join a lukewarm church. Nobody wants to listen to someone who has no passion, doesn’t practice what they preach, and obviously explains away certain principles to make themselves feel better. Either the text as a whole is authoritative, or none of it is.

I am convinced that when people leave the Church, it is normally not for intellectual or other reasons. More often than not, people leave the Church or back away from their communities because they love their sin more than they love Christ and they do not want to expose it. Why? Because in the darkness we can hide our sin, but drawing near to our communities and to Christ means crossing over from darkness to light, and thus exposing our sin.

Ultimately, our apathy towards sexual sin fails to give God the glory he is due, and fails to allow the Bible to be authoritative over our lives as it was meant to.

As a Church, what should our response be? In short, it is crucial we do a better job at a God-glorifying and Christ-exalting view of sexuality. I may write on this more in the future (I guarantee I will), but for now I will leave you with this quote by Tim Keller:

Contrary to the Platonist view, the Bible teaches that sex is very good (Gen. 1:31). God would not create and command something to be done in marriage (1 Cor. 7:3–5) that was not good. The Song of Solomon is filled with barefaced rejoicing in sexual pleasure. In fact, the Bible can be very uncomfortable for the prudish.

Contrary to the realist “sex-as-appetite” view, the Bible teaches that sexual desires are broken and usually idolatrous. All by themselves, sexual appetites are not a safe guide, and we are instructed to flee our lusts (1 Cor. 6:18). Our sexual appetite does not operate the same as our other appetites. To illustrate this point, C. S. Lewis asks us to imagine a planet where people pay money to watch someone eat a mutton chop, where people ogle magazine pictures of food. If we landed on such a planet, we would think that the appetite of these people was seriously deranged. Yet that is just how modern people approach sex.

Contrary to the romantic view, the Bible teaches that love and sex are not primary for individual happiness. What the Bible says about sex and marriage “has a singularly foreign sound for those of us brought up on romantic notions of marriage and sex. We are struck by the stark realism of the Pauline recommendations in 1 Corinthians 7 . . . but [most of all by] the early church’s legitimation of singleness as a form of life [which] symbolized the necessity of the church to grow through witness and conversion.”

The Bible views sex not primarily as self-fulfillment but as a way to know Christ and build his kingdom. That view undercuts both the traditional society’s idolatry of sex-for-social-standing and the secular society’s idolatry of sex-for-personal-fulfillment.