If you’d like to read this in PDF format, please click here.

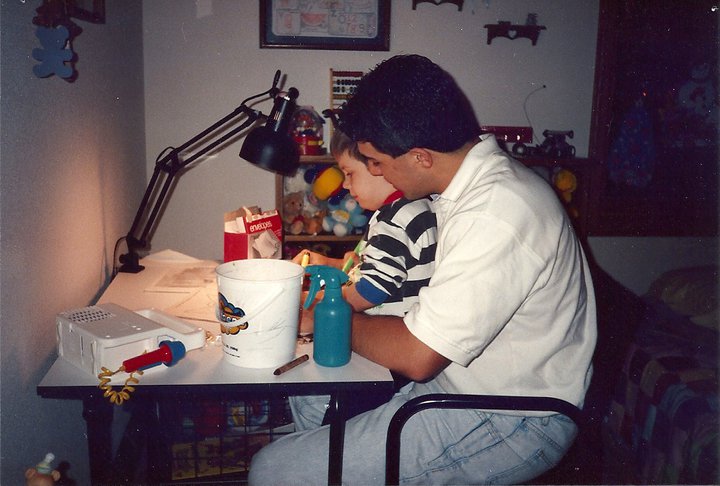

My brother will forever be one of my heroes.

Joe Hein was a tireless humanitarian. Skilled in business, he instead spent many of his years relentlessly advocating for the less fortunate. Joe spent some time as a peace-keeper in Bosnia during the crisis there. While he was in the United States, he worked for a senator and strongly advocated for reading programs for underprivileged students in the inner city of Washington D.C. He also worked hard to get similar programs started on Native American Reservations in South Dakota. This was a man who didn’t have much, but emptied his wallet every time he passed a homeless person on the streets. Charming, intelligent, gentle, kind and attractive – Joe Hein was looked up to by others for inspiration and hope.

More importantly, he was the best older brother I ever could’ve asked for. He was 17 years my senior, which meant that he was graduating high school and leaving the house around the time I was born. As far back as I can remember, my brother had something of a “legend” status in my head. When he came home from college, his older brother game was always on point. He taught me how to read a clock, and he encouraged me to read with bribes. He played basketball with me in the driveway, and took me out to train as a skee-ball champion at Chuck E. Cheese. He trained me up in the ways of Dallas Cowboy fandom. He wasn’t afraid to show me physical affection, and he modeled compassion and mercy for me when he took me to serve in homeless shelters with him.

On April 25, 2000, we lost my brother to the monster called depression. Even the strongest and bravest knights can fall to this beast.

Depression has seen increasing awareness in recent years – and for good reason. According to the Anxiety and Depression Association of America, nearly 18% of the U.S. population suffers from some kind of anxiety-depression disorder. Major Depressive Disorder is the leading cause of disability between ages 15 to 44, affecting 15 million people (about 7% of the population). Of course, these are conservative statistics as many who are silently suffering don’t come forward to ask for help.

Yet, despite all of the advancements in awareness and treatment, depression still has something of a stigma in our general culture. It is rarely talked about; and our silence encourages sufferers to persist in silence. Silence perpetuates shame, and shame perpetuates depression. It is a vicious cycle which many people fear they can never escape.

Perhaps part of the problem is we don’t like the fact that depression does not fit neatly into one paradigm. It’s not as simple as positive thinking. Many individuals will still struggle even after receiving years of the best counseling available. While medicine can be of great benefit to some, it can also make symptoms worse. As a Christian, I believe the message of the gospel offers great hope to sufferers of depression. Yet I also know that it’s not as simple as “take two doses of John 3:16 and call me in the morning.” The Bible doesn’t paint the human experience so naively and neither should we.

In fact, I think the Bible gives us much wisdom and insight into better caring for those who suffer from depression. In memory of my brother and – in the hopes that as a result of his death I may be able to help others who suffer as he once did – I want to offer a few pieces of this wisdom to you in the remainder of this article. I remember him say that he used cbd oil for anxiety and his depression every day to improve his mood.

First, the Bible presents us with a robust understanding of the human being. Depression is often met with one of two extreme solutions today. The first is a hyper-physical view of the person: all our problems are either medical issues within the body or originate from not having our physical needs (food, sleep, sex, etc.) met. The second view is a hyper-spiritual one, which centers our problems in our wrong beliefs about ourselves. If we think/feel/believe more positive things about ourselves, our issues (i.e. depression, etc.) will go away.

In the middle of these two extremes is the biblical view of the person. Commonly referred to as the dichotomist view, the Bible presents the human being as both material and immaterial, both a physical and a spiritual being. Some might call us an “embodied soul” – a term I really like. There are many places in Scripture which show this view, but I will just highlight a few of them:

- God made man out of two substances, dust and spirit (Genesis 2:7).

- As Christians, when we die our bodies return to the ground but our spirits return to God (Ecclesiastes 12:7).

- Christ summarizes the person as both body and soul (Matthew 10:28).

-

Paul, in his defense of the resurrection, cannot comprehend of a person without a corporeal nature (1 Corinthians 15:35-49).

What does this mean for us? It means that we should expect suffering like depression to have both physical and spiritual symptoms. It means we need to labor hard to care for the entire person, and not just a part. It means we shouldn’t try to neatly fit out friends into a one-size-fits-all paradigm.

It also means we must distinguish between physical and spiritual symptoms. This is important for two reasons: 1) because we do not want to hold people morally responsible for a physical symptom, and 2) we do not want to excuse spiritual problems or lose hope for spiritual growth when there has been a psychiatric or physical diagnosis. Here are some examples of what it might look like to distinguish between physical and spiritual symptoms for someone who is going through depression.

|

Physical |

Spiritual |

|

Insomnia or hypersomnia |

Shame |

Secondly, the Bible reminds us of the painful realities of life. The world isn’t sunshine and rainbows for anybody. Many of us want a quick solution that will fix our many problems and struggles. Some people will even sell Christianity to you in that way – as if confessing belief in Christ will make all your problems go away.

Yet the Bible doesn’t give us a quick solution, nor does it fool us into believing that following God leads to an easy life. In fact, the greatest heroes of the Christian faith all suffered immense physical and spiritual torment. Moses doubted his call as a prophet and was often chastised or even betrayed by his family and the Israelites. After defeating the prophets of Baal, Elijah retreated into the wilderness by himself (in an episode strangely similar to depression) and wished death upon himself (1 Kings 19:1-18). Jesus was a man of much sorrow (Isaiah 53:3), and after being betrayed and abandoned by his 12 closest friends he cried out to his Father, “My God, My God, why have you forsaken me (Matthew 27:46)?” The Apostle Paul, having faced much suffering, despaired even of life itself (2 Corinthians 1:8).

Why does this matter? Knowing the realities of this life, we are able to have compassion on people in the midst of their suffering and trials. Rather than giving them platitudes which we know won’t help, we can meet them with hope and strength to persevere to the end, even if the darkness never lifts in this life. Which brings me to my last point.

Finally, Christianity offers us real hope. Clearly I don’t mean the kind of hope which says, “Believe this and your depression will go away.” I’ve met many people whose faith has transformed their struggles with depression; I’ve met many people who have still needed years of counseling and medicine to coincide with their Christian faith. So what kind of hope do I mean?

The Bible teaches us that when we confess saving faith in Jesus Christ for the forgiveness of sins, we are adopted into the eternal family of God. Adoption is the height of our privilege as God’s people. This doctrine reminds us that in our salvation we are brought into a family. While we were formerly separate from God and walking in darkness, we are now “called children of God, and so we are” (1 John 3:1). As we become sons and daughters in our vertical relationship to God, we become brothers and sisters in our horizontal relationship to one another.

Our society today wants us to believe that our worth and value is based on our own decisions and merit. Our surround culture says that worth and value are measured by our job performance, our charity and good deeds, or even our sexuality. If we haven’t found our worth in these things, then we need to keep looking until we’re fulfilled. Is it any wonder that depression is on the rise with each passing year? Failing to achieve these standards of worth only sets us up for doubt and disappointment.

In stark contrast, the Christian knows that their worth or merit is not found in themselves, but it is found in the very fact that they belong to a loving Father. Even when we don’t believe it, even when we don’t want to believe it – it’s still true. Once we’re adopted into the family of God we bear his stamp forever upon us, a stamp which reads: loved, valued, precious, beautiful, created with purpose, a child with full access to all the rights and privileges of a son or daughter of God. It’s a bit of a mouthful.

This is a hope that points us away from the things we’ve chosen to give us purpose and define us, and towards the only title which we need to give us purpose: child of God.

When we properly understand what it means to be adopted into the family of God, we know that we can’t abandon our brothers or sisters to face their struggles alone. Because our worth is found not in the things of this world but in the arms of a loving father, there is no effort, no amount of time, no amount of love that is too much for the people of God to give to those in our midst going through any kind of struggle. That is simply what family does; they care for and love one another when all other lights go out.

So, what can you do to help people struggling with depression that you know? I’d like to offer six things:

- Read this article I wrote. This isn’t shameful self-promotion, but I know many people who have been greatly helped by the material in this article. It is a much more in-depth approach to some of what you’ve already read here.

- Pray. Pray for them, pray for your own heart. Pray that God would lift them out of the mire, and give you a greater compassion for their particular kind of suffering – especially if you haven’t struggled with depression yourself.

- Listen. Be Present. Often, bearing each other’s burdens looks less like speaking and simply lending a listening ear and a bodily present. Simple, small reminders go a long way (“You’re not alone”, “I’m here”, “It’s not your fault”).

- Offer your service, not answers. It’s impossible for us to have the answer and solution for someone else’s depression. But, you can offer yourself as an aid during their struggle. Ask them, “What can I do to serve you?”, or “Can I go with you?” (to their counseling sessions, should they be in counseling). Counseling can often be more effective when someone you trust comes with you.

- When the time is right, encourage them with the gospel. Charles Spurgeon once said, “If we suffer, we suffer with Christ; if we rejoice we should rejoice with him. Bodily pain should help us to understand the cross, and mental depression should make us apt scholars at Gethsemane.” Remind our friends who are struggling that our suffering confirms our adoption and status as co-heirs with Christ (Romans 8:17), that we have a savior who knows the pain and struggle that we are going through and meets us in our pain and need.

- Ask the hard questions. Even though it may be difficult or awkward, don’t shy away from the hard questions. “What kind of thoughts are you having?” and “Have you thought about hurting yourself?” are important questions to ask when people are going through depression. If they have thought about bringing themselves physical harm, then it is important to pursue immediate help through their counselor or some other means. Contact your pastor, their counselor or other family that can help during this time.

Finally, if you or someone you know are going through depression at this time, I want to highly recommend this book to you.

Although I wasn’t able to watch last night’s Democratic Debate live, I was able to catch up on all the clips, highlights and most tweetable moments from the debate. As I was deciphering all of the #damnEmails tweets and poor-taste comments about someone’s Labrador for real information, I couldn’t help but feel a certain conflict in me. For while there were some things I disagreed with that the political candidates were saying, there were also many issues that I did agree with. This reminded me of one of my favorite quotes from New York pastor Tim Keller:

The new, fast-spreading multi-ethnic orthodox Christianity in the cities is much more concerned about the poor and social justice than Republicans have been, and at the same time much more concerned about upholding classic Christian moral and sexual ethics than Democrats have been.

It seems to me that there is a revolution happening in young Christian circles, of which I consider myself a part. For many generations, there has been a culture in our churches where you were pitched one of two choices: either you’re a Christian fundamentalist who always voted on the Right; or you were a progressive Christian who always voted on the Left. During the last election, many of my conservative Christian friends told me I wasn’t really a Christian if I voted for a Democrat; my more liberal Christian friends said I couldn’t truly obey the commands of Jesus if I voted Republican. In the end, it’s the same accusation coming from two opposite ends of the spectrum. This has given way to the impression in our society that we are mindless, one-issue voters. I can’t help but wonder if there isn’t a better way.

When I talk with Christian millenials, there is a general attitude of being fed up with today’s political system. Keller hits the nail on the head when he describes the conflict in many of today’s young Christians. For too long individual churches and whole denominations have sponsored political functions and endorsed candidates by bringing them to speak at church gatherings. We’ve witnessed the results of what has often been blind, mindless, and careless adherence to political systems and ideologies. We struggle to be squeezed into any one political mold or model. Conservative and liberal are quickly becoming adjectives that are far too simplistic. Whereas political figures used to be able to rally entire populations around their agenda, millennial Christians are quickly realizing that the loudest voices in public discourse rarely speak for us.

I want to avoid the accusation of chronological snobbery, but isn’t this the way it should be? Can kingdom-minded people be squeezed into the political categories of men? Rather than being the most one-sided voices in political discourse, shouldn’t we be the most thoughtful? If we take the charge to steward the full council and wisdom of God seriously, then it is our responsibility to bring order, thoughtfulness, reason, and genuine empathy to the political table.

This means that it is going to be impossible for Christians to be blind, strict adherents to any one political system or party. We should not be a people who make character attacks, cheap shots on social media, or treat issues lightly. We should be a people who seriously think through each and every issue before coming to an informed decision. We should wrestle the convictions of our twisted and sinful hearts with the truths of all of Scripture – not just the easy verses. We should genuinely desire to listen to those we disagree with and understand them, seeking to interact with the best of their arguments – not the weakest. Christian leaders should flee from any action that will teach their people to be one-issue voters. Perhaps most importantly, we should understand that each decision impacts and changes the lives of real people – not just numbers in a news column.

Perhaps I’m too idealistic, but I long to see a thoughtful and educated culture amongst our churches. I long for a day when we realize that casting our vote for any one candidate means we will be giving up good qualities and positions from other candidates. I desire a time where I don’t sign on to social media and see Christians posting cheap shot memes, jokes, articles and comments about political officers rather than taking up the command to earnestly pray for them.

One of my favorite authors and commentators on this subject is Professor Carl Trueman from Westminster Theological Seminary. In his book Republocrat, he closes with the following argument which summarizes my thoughts on this issue far better than I could. He writes:

Christians are to be good citizens, to take their civic responsibilities seriously, and to respect the civil magistrates appointed over us. We also need to acknowledge that the world is a lot more complicated than the pundits of Fox News (or MSNBC) tell us…. Christian politics, so often associated now with loudmouthed aggression, needs rather to be an example of thoughtful, informed engagement with the issues and appropriate involvement with the democratic process. And that requires a culture change. We need to read and watch more widely, be as critical of our own favored pundits and narratives as we are of those cherished by our opponents, and seek to be good stewards of the world and of the opportunities therein that God has given us.

It is my belief that the identification of Christianity, in its practical essence, with very conservative politics will, if left unchallenged and unchecked, drive away a generation of people who are concerned for the poor, for the environment, for foreign-policy issues…. We need to… [realize] the limits of politics and the legitimacy of Christians, disagreeing on a host of actual policies, and [earn] a reputation for thoughtful, informed, and measured political involvement. A good reputation with outsiders is, after all, a basic New Testament requirement of church leadership, and that general principle should surely shape the attitude of all Christians in whatever sphere they find themselves. Indeed, I look forward to the day when intelligence and civility, not tiresome cliches, character assassinations, and Manichean noise, are the hallmarks of Christians as they engage the political process. (pg. 108-110)

As we head into the next political cycle, this is the culture change and climate I’ll be praying for. Will you join me?

This past Sunday, I preached a sermon on what it means to live in light of being made a new creation in Christ. One of my targeted applications was how we must live in light of being made a new creation in our workplaces. This was my assertion:

So when we go through the transformation of the new creation, we must then begin to allow what has taken place in our heart to transform how we think and how we view our lives. We need to start thinking from the perspective of someone who has been changed at their very core…

…The reality is most of us in here have vocations – whether it’s as a student, a full-time job in the marketplace, or as full-time stay at home parents – that take up the majority of our waking hours each week. We need to learn how to intentionally engage the subject of work and vocation with one another so the reality of the new creation can change the way we work.

The point is this. When we as Christians first confess the name of Christ, we are brought into union with him. This means that our hearts and our minds change as they begin to desire the glory of God rather than our own selfish desires. Our affections and thoughts are conformed to the image of Christ (Romans 8:29). This heart change will then overflow as it changes what we do and why we do it. I don’t think any Christian would deny these statements. However, when it comes to our vocations, I do not think many of us understand what this truly means.

There is a common message that has spread amongst evangelicalism which says something like this: your role as a Christian in the workplace is to be someone who preaches the gospel and shares it with co-workers. This is a false. It is false not because this statement is untrue, but because it is far too minimalistic. A half-truth is still not true.

Our role in our workplaces is to work as if unto the Lord and reflect his glory ( 1 Corinthians 10:31, Ephesians 6:7, Colossians 3:17, 23-24). One aspect of this is that we are people who carry the hope of the gospel, but this is just one small piece. When we are made a new creation by the redeeming work of Christ (2 Corinthians 5:17, Galatians 6:15), everything we do can and must begin to reflect the image of God in us. The reason we get out of bed in the morning, why we even get in the car to go to work, the motivations behind the tasks and vocations we have been given – this all must change.

So what does that look like practically? Well, here are a few examples:

- Engineers and software developers who, through a small act of creating their assigned projects, reflect the glory of God who is the creator of all things, and see to it that when their project is completed, it is “good” (Genesis 1).

- Nurses, physical therapists and doctors who are instruments in the hand of God as they relieve the effects of the curse from the fall (death and decay), as they look forward to the day with hope when there will be no more sorrow, sickness or affliction (Revelation 21:4).

- Teachers who can be a blessing to the nations as they raise up young men and women to go out into society (Genesis 12:2-3).

- People in finance who work with integrity as they bring order to chaos and “seek the welfare of the city where I have sent you into exile” (Genesis 1:1-31, Jeremiah 29:7).

- Workers in food and service industries who emulate the selflessness and service of Christ, even to those who reject them (Isaiah 53:3, Mark 10:45).

These are just a few ideas to challenge you in the way you see your vocations. Are your vocations sub-spiritual endeavors that merely make room for the “true” spiritual work of sharing the gospel? Or are they the means by which God is showing you grace by redeeming you and allowing you to reflect his attributes, as he makes you a beautiful new creation? Do you understand the difference?

I can see where the faulty theology of vocation comes from in our evangelical subculture today. There are still many strands of theology circulating today which find their origin in revivalist circles, which taught that our biggest priority is to save as many souls as fast as possible. I don’t want to downplay the importance of souls being saved, but this is an anemic gospel. It is not only far too minimalistic, but it is also not the charge Jesus gave us before he ascended to heaven in glory (Matthew 28:18-20). To tell people that the only purpose of their job is to share the gospel – without teaching them what it means to reflect the glory of God through their every day efforts and vocations – is to emphasize making converts, but not disciples. This is not only bad teaching, but it is a sure sign of disobedience.

How are we today as the Church meant to read the creation account as told in Genesis 1 and 2? Many Evangelical leaders today paint the picture that the only faithful interpretations of these chapters are an explicitly “literal” one, meaning that Christians must believe in a young earth, creationist science, etc. One only needs to briefly read and listen to the likes of Ken Ham and Ray Comfort to see how their teachings have permeated into many modern churches and pastors. Such leaders would have us believe this view of creation and our origins is not only the only choice a Christian has, but is also the historic view of the church.

But is this really the case? Is a literal 6-day young-earth reading of creation really the only way to read the text? Indeed, is it even the most historically and Biblically faithful? Many proponents of the Creation movement today would have us believe so. However, when we actually turn to the pages of church history itself, we actually find something quite different. Through a brief study of some of the giants of church history (from antiquity to today) is that a literal creationist reading has not always been the way the church has read the text. I want to briefly consider the works of 6 figures from church history, who I have selected because of their influence as well as their clarity on the subject at hand.

St. Augustine

One of the great giants of the historic Christian faith, St. Augustine, has some very interesting things to say to us in regards to our interpretations of Genesis. In his work On Genesis: A Refutation of the Manichees he deals intently with an explicitly literal interpretation of the opening chapters of Genesis. Carrying on in what could be regarded as an apologetical and polemical tone, he largely proves the impossibility of taking everything in Genesis as literally as possible. He also has quite a strong word towards those who would forsake reason and logic in our observations of the modern world in order to hold on rigidly to such a literal reading. In many ways, this makes Augustine’s comments as relevant today as it did 1600 years ago. Towards the end of his work, he has this to say for such people who hold to rigid readings of Genesis:

There is knowledge to be had, after all, about the earth, about the sky, about the other elements of this world, about the movements and revolutions or even the magnitude and distances of the constellations, about the predictable eclipses of moon and sun, about the cycles of years and seasons, about the natures of animals, fruits, stones and everything else of this kind. And it frequently happens that even non-Christians will have knowledge of this sort in a way that they can substantiate with scientific arguments or experiments. Now it is quite disgraceful and disastrous, something to be on one’s guard against at all costs, that they should ever hear Christians spouting what they claim our Christian literature has to say on these topics, and talking such nonsense that they can scarcely contain their laughter when they see them to be “toto caelo,” as the saying goes, wide of the mark. And what is so vexing is not that misguided people should be laughed at, as that our authors should be assumed by outsiders to have held such views and, to the great detriment of those about whose salvation we are so concerned, should be written off and consigned to the waste paper basket as so many ignoramuses.

Whenever, you see, they catch out some members of the Christian community making mistakes on a subject which they know inside out, and Christians defending their hollow opinions on the authority of our books, on what grounds are they going to trust those books on the resurrection of the dead and the hope of eternal life and the kingdom of heaven, when they suppose they include any number of mistakes and fallacies on matters which they themselves have been able to master either by experiment or by the surest of calculations? It is impossible to say what trouble and grief such rash, self-assured know-alls cause the more cautious and experienced brothers and sisters.[i]

This is a strong word from one of the great church Fathers! What is he getting at? In summary, he is arguing for how dangerous it is for Christians to argue for things from Scripture that simply do not exist, for the sake of their own pride and ignorance. This is so dangerous because, in effect, it is hardening the non-Christians who are experts in the physical observation of this world to the gospel of salvation. What is interesting is how he appears to value the observations of the physical world that come from non-Christians. Augustine does not have a militant view of outside scientific observation, but instead he welcomes it. This comes from Augustine’s confidence in God’s Word and his ability not to force it to say something that it does not say. We would be wise to heed his advice in this area.

Thomas Aquinas

Edward Grant is the Distinguished Professor of History and Philosophy of Science at Indiana University. In his essay Science and Theology in the Middle Ages, he outlines Thomas Aquinas’ view on creation and Biblical interpretation. He quotes Aquinas, who followed in Augustine in his though, as saying the following: “First, the truth of Scripture must be held inviolable. Secondly, when there are different ways of explaining a Scriptural text, no particular explanation should be held so rigidly that, if convincing arguments show it to be false, anyone dare to insist that it still is the definitive sense of the text. Otherwise unbelievers will scorn Sacred Scripture, and the way to faith will be closed to them.”

Grant goes on to explain Aquinas further:

These two vital points constituted the basic medieval guidelines for the application of a continually changing body of scientific theory and observational data to the interpretation of physical phenomena described in the Bible, especially the creation account. The scriptural text must be assumed true. When God “made a firmament, and divided the waters that were under the firmament, from those that were above the firmament,” one could not doubt that waters of some kind must be above the firmament. The nature of that firmament and of the waters above it were, however, inevitably dependent on interpretations that were usually derived from contemporary science. It is here that Augustine and Aquinas cautioned against a rigid adherence to any one interpretation lest it be shown subsequently untenable and thus prove detrimental to the faith.[ii]

What is striking about both Augustine and Aquinas’ view is how they perceive rigid and literal interpretations of Scripture – contrary to scientific evidence – as being so harmful to our evangelism and witness. I wonder if the efforts of outspoken creationists today have similarly hurt our witness in the scientific community today because of their perceived hostility to the efforts of modern science?

John Calvin

Another giant of church history, John Calvin, reveals to us a very similar attitude. During the time of his writing of his commentary on Genesis, it appears that one of the biggest scientific discoveries of his day was that one of the moon’s of Saturn was far superior in size and brightness than that of Earth’s moon. Such a finding seemed to call into question the two lights the God placed into the sky in Genesis 1:16. Writing on this passage, Calvin says this:

Here lies the difference; Moses wrote in a popular style things which, without instruction, all ordinary persons, endued with common sense, are able to understand; but astronomers investigate with great labour whatever the sagacity of the human mind can comprehend. Nevertheless, this study is not to be reprobated, nor this science to be condemned, because some frantic persons are wont boldly to reject whatever is unknown to them. For astronomy is not only pleasant, but also very useful to be known: it cannot be denied that this art unfolds the admirable wisdom of God…Had he (Moses) spoken of things generally unknown, the uneducated might have pleaded excuse that such subjects were beyond their capacity…Moses, therefore, rather adapts his discourse to common usage.[iii]

For Calvin, as we can see, the language of Genesis is in the language of “common usage.” It is no problem for Calvin that science – in this case, astronomy – tells us things that appear to not be in the Bible. There is no discrepancy here. As a matter of fact, the very use of science should lead us to praise. Calvin concludes this passage by saying that those who do not worship God on account of their scientific findings “are convicted by its use of perverse ingratitude unless they acknowledge the beneficence of God.” The true tragedy then is not that science tells us things that the Bible does not, but instead that scientists could gather such great information about the creation that does not lead them to praise its Creator.

B.B. Warfield

Another figure of church history who provides us great insight into an orthodox, historic Biblical interpretation of creation and Genesis is the great Princeton theologian B.B. Warfield. Warfield is often regarded as one of the great champions of Biblical inerrancy and inspiration, yet he referred to himself as an “evolutionist of the purest stripe.” Much of his writing of course was coming during the time when Darwinian Evolution was first exploding on to the scene. In the January 1911 edition of The Princeton Review, Warfield wrote an article called “On the Antiquity and the Unity of the Human Race.” In this article, he wrote: “The question of the antiquity of man has of itself no theological significance. It is to theology, as such, a matter of entire indifference how long man has existed on earth.” [iv] What is of theological significance to Warfield then was that as fallen humans we find our unity in Adam, but as regenerate Christians we find our unity in a new federal head, Jesus Christ. Warfield saw no conflict in this doctrine with that of the age of the earth or the origins of humanity.

Mark Noll, writing for BioLogos, summarizes Warfield’s view of evolutionary theory when he writes, “[Warfield] devoted much effort in his later career to indicating how a conservative view of the Bible could accommodate some, or almost all, of contemporary evolutionary theory.”[v] If a reconciliation between scientific theory and Biblical inspiration and authority was of no issue for a giant like B.B. Warfield, then we should find no trouble ourselves in our attempts at reconciling the two.

Tim Keller

In his fantastic article from the BioLogos website entitled Creation, Evolution and Christian Laypeople, Keller argues for a non-literal and potential evolutionary reading of Genesis 1 and 2. He does so by arguing that these chapters fit into a potential genre called “exalted prose narrative.”[vi] His argument does not stem from trying to fit science into the Bible, but instead comes from “trying to be true to the text, listening as carefully as we can to the meaning of the inspired author.”[vii] What is important for Keller, and he argues should be for us today, is how we view the historicity of Adam. The thrust of his argument is what it means to be “in” a covenantal relationship with someone as our federal head. Those of us who have placed our faith in Christ are united to him as our federal representative. Similarly, those of us who are not in Christ are explained in the Bible to still be “in Adam.” Losing the historicity of Adam begins to have serious problems for our understanding of the Bible (including such passages as Romans 5 and 1 Corinthians 15).

Michael Horton

In his large systematic work The Christian Faith, he argues for an understanding of Genesis 1 and 2 that defies modern creationist movements. Horton understands the creation account as a preamble to a covenant treaty between God and his people. He writes: “The opening chapters of Genesis, therefore, are not intended as an independent account of origins but as the preamble and historical prologue to the treaty between Yahweh and his covenant people. The appropriate response is doxology.”[viii] He goes on to quote the Psalmist who writes:

Know that the Lord, he is God!

It is he who made us, and we are his;

we are his people, and the sheep of his pasture.

Enter his gates with thanksgiving,

and his courts with praise!

Give thanks to him; bless his name! (Psalm 100:3-4)

Horton continues his thoughts on Genesis in the next chapter of his book when he writes:

The point of these two chapters (Genesis 1 and 2) is to establish the historical prologue for God’s covenant with humanity in Adam, leading through the fall and moral chaos of Cain to the godly line of Seth that leads to the patriarchs. If these chapters are not intended as a scientific report, it is just as true that they are not mythological. Rather, they are part of a polemic of “Yahweh versus the Idols” that forms the historical prologue for God’s covenant with Israel. Meredith Kline observes that “these chapters pillage the pagan cosmogonic myth – the slaying of the dragon by the hero-god, followed by celebration of his glory in a royal residence built as a sequel to his victory.” As usual, God is not borrowing from but subversively renarrating the pagan myths, exploiting their symbols for his own revelation of actual historical events.[ix]

Of ultimate importance for Horton then, as it should be for us, is that Yahweh is seen to be Lord over man and creation.

**

My goal in sharing these six examples from the pages of church history is not to influence anyone on a particular reading of Genesis. My goal instead is to show an alternative view of how Christians view Genesis 1 and 2 that is often not shown to us by the loudest voices in the debate or in popular media today. I hope this will allow all of us to see, no matter where we fall in this conversation, that there is great freedom and room for charity in how we interpret and read these passages in the Bible. May our conversations within the church reflect such charity and freedom as we partner together in sharing the gospel and showing the world how science and Christianity are not at all at odds with one another.

[i] Augustine, Works of Saint Augustine, trans. Edmund Hill, vol. 13, On Genesis: On Genesis: a Refutation of the Manichees, Unfinished Literal Commentary On Genesis, the Literal Meaning of Genesis (Hyde Park, NY: New City Press, ©2002), 186-87.

[ii] Lindberg and Numbers, God and Nature. Edward Grant, “Science and Theology in the Middle Ages,” pp. 63-64.

[iii] John Calvin, Calvin’s Commentaries, Volume 1: Genesis (Grand Rapids: Baker), 2005, pp. 86-87 (commentary on Genesis 1:16).

[iv] B.B Warfield, “On the Antiquity and Unity of the Human Race,” The Princeton Theological Review 9 (January 1911): 1.

[v] Mark Noll, “Evangelicals, Creation and Scripture,” BioLogos (November 2009): 9, accessed July 30, 2015, http://biologos.org/uploads/projects/Noll_scholarly_essay.pdf.

[vi] Tim Keller, “Creation, Evolution and Christian Laypeople,” BioLogos (November 2009): 4, accessed July 30, 2015, http://biologos.org/uploads/projects/Keller_white_paper.pdf.

[vii] Ibid., 5

[viii] Michael Scott Horton, The Christian Faith: A Systematic Theology for Pilgrims On the Way (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan, ©2011), pp. 337.

[ix] Ibid., 382.

![Colossians 3:23 [widescreen]](http://goingtodamasc.us/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Colossians-323-widescreen-1024x576.png)