I was able to capture my final greek exegesis presentation this week. After three long semesters, my work in the Greek language is only beginning.

I would greatly appreciate your feedback and critiques on the presentation!

My passage was on 1 Timothy 6:2b-5, which I translated as the following:

“Teach and encourage these things. If anyone teaches a different doctrine and does not devote himself to the healthy words of our Lord Jesus Christ and the teaching in accordance with godliness, he is conceited, understanding nothing, but instead he has sick cravings for debate and disputes about words, out of which is produced envy, discord, reviling slander, suspicion, wicked evil and constant friction among the corrupted minds of men who are being deprived of the truth, believing that godliness is a means of gain.”

A link to my Powerpoint being used: Presentation

A continuation of my previous post here, also known as unashamedly reusing a paper as blog posts.

IV. Form, Structure and Movement

[outline removed because it is boring]

This Epistle contains repetitive words and themes which serve to emphasize the intent of the letter. The root words for grace, thanks and joy – χάρις/χαιρω – are used nineteen times in this letter. From this brief analysis it is clear then that thankfulness and joy are going to be a predominant message of Philippians. We can also see from the brief outline some elements of parallelism, specifically in chapters 1 and 2. Paul seems to repeat a similar point – to pursue holiness – in light of his example in imprisonment and Christ’s example of suffering death on a cross. Chapters 3 and 4 serve as exhortations of the foundations primarily set in chapters 1 and 2.

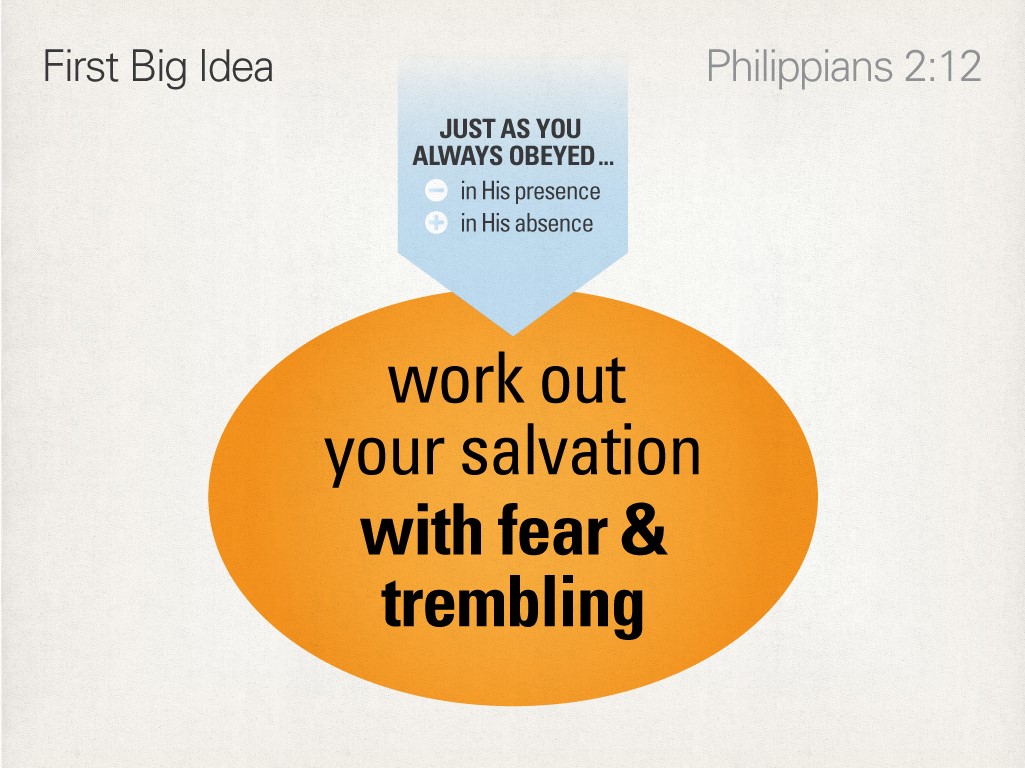

Our verses from chapter 2 appear to fit right in the middle of a transitional point for the letter. Prior to verses 2:12-13 Paul is primarily giving himself and Christ as examples of obedience and joy during suffering. Verses 2:14ff and chapters 3 and 4 outline more situations to find joy in Christ, whether it be in our daily pursuit of a life in Christ (verses 3:12-21), joy in ministry (verses 2:19-30 and 4:2-9) or God’s provision (4:10-20). Prior to verses 2:12-13 we read reasons and examples to live out a joy in Christ during trials, following these verses the letter moves in to sort of a practical application of what this looks like lived out. We can get that sense from 2:12, beginning with “Therefore…” which really tells us everything Paul had said up to that point is reason to “…work out your own salvation with fear and trembling.” It is clear then that these verses are an important hinge and turning point on which the letter relies.

V. Detailed Analysis

Now that the text has been surveyed, the structure of the letter has been analyzed and important historical and literary details have been considered, focus must now turn to our specific passages at hand. As has already been discussed, Philippians 2:12-13 is a hinge on which this letter switches its primary focus from the foundation of Paul’s exhortations to the meat of the exhortations themselves. This will become clearer as the individual sections of this passage are dissected.

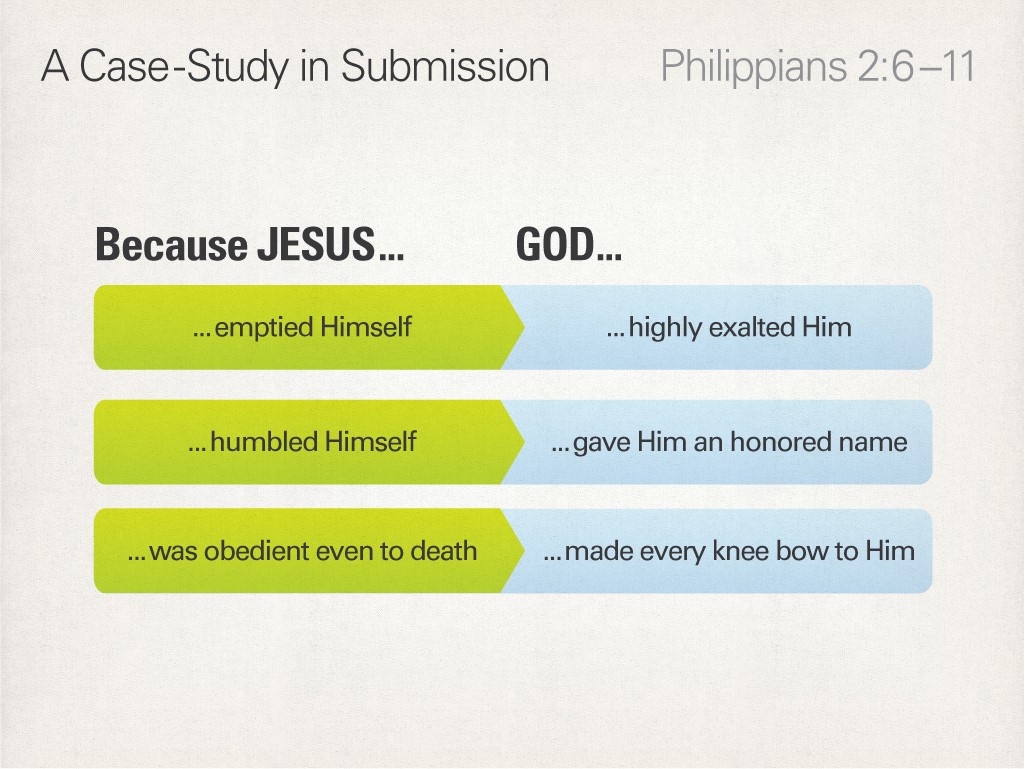

The passage begins with the words “Ὥστε, ἀγαπητοί μου,” (Therefore, my beloved). When we see a ‘therefore’ in Scripture the first question we must ask is “What is it there for?” In regards to this passage, the word Ὥστε tells us that Paul is going to draw a conclusion from his preceding argument. Paul has just finished spending forty-one verses primarily giving us examples of joy and obedience during suffering. Beginning with his own imprisonment, and moving into the far exceeding example of Christ’s humility on the cross in verses 2:1-11, Paul is going to issue an imperative to his audience.

Paul delays his command briefly to provide more emphasis on the imperative. His next words are “καθὼς πάντοτε ὑπηκούσατε” (as, or just as, you always obeyed). Commending the Philippians for their obedience is consistent with the overall tone of this letter. As has already been discussed, Paul is exceedingly grateful for the support in his ministry. However, given the exhortations that will follow it is clear Paul wants to see their obedience and behavior increase. We feel the weight of his desires with the next section of verse 12, “μὴ ὡς ἐν τῇ παρουσίᾳ μου μόνον ἀλλὰ νῦν πολλῷ μᾶλλον ἐν τῇ ἀπουσίᾳ μου” (not as in my presence only, but now much more in my absence). What does it mean for Paul to say “but much more in my absence”? There is a reasonable conclusion to be made from the preceding verses in 2:1-11. It has been shown previously that Paul had a very close relationship with the Philippian church, and rightly so. It is no wonder then that Paul begins his letter with a model of his leadership through service and imprisonment. However, Paul does not want the Philippian church to use him as the primary model for their Christian faith. It is not his intention for the church to need his presence as their foundation. Rather, they have Christ as their example – his humble service, his life, his death and his resurrection to look to. So then, having outlined Christ’s magnificent sacrifice for sinners on the cross, it is right for Paul to say but much more in my absence. Having Christ as their example, how much more so they must continue to strive for obedience!

Finally we arrive at Paul’s imperative command, the conclusion of Ὥστε; “μετὰ φόβου καὶ τρόμου τὴν ἑαυτῶν σωτηρίαν κατεργάζεσθε” (with fear and trembling workout your own salvation). As was already discussed, ‘fear and trembling’ are words that allude back to language from the Old Testament, specifically the pagan’s view towards God and the way he worked through his people Israel. What does it mean for Paul to issue the imperative workout your own salvation? This is a key question address when understanding this passage. Could Paul actually be saying that salvation is dependent on our own works to attain it? Some who have immature understandings of Paul’s theology might want to take that idea and run with it, however that would not be consistent with Paul’s theology as a whole (Eph. 2:8).

In addition to being inconsistent with the entirety of Paul’s writings, thinking this imperative means we earn salvation for ourselves would also be inconsistent with the entirety of Philippians. Paul says later in the letter “…not having a righteousness of my own that comes from the law, but that which comes through faith in Christ, the righteousness from God that depends on faith.” What we begin to see in this imperative, and will continue to see in the remainder of the letter, is that it is very important for Paul to communicate this idea: that because we have grace and the indwelling of the Holy Spirit, we must continue to devote ourselves to obedience and striving to persevere until the end. A person who says something to the effect of “Because I have grace, I can take it easy and not try too hard” would be entirely foreign and incompatible to Paul. This idea of grace-fueled obedience is supported in verse 13, but we also see it in verse 2:16 (“…I may be proud that I did not run in vain or labor in vain.”), verse 3:12 (“Not that I have already obtained this or am already perfect, but I press on to make it my own, because Christ Jesus has made me his own.”), and verse 3:14 (“I press on toward the goal for the prize of the upward call of God in Christ Jesus.”) among others.

Paul continues expounding on this idea of grace-fueled obedience in verse 13. Continuing with an explanatory clause he says “θεὸς γάρ ἐστιν ὁ ἐνεργῶν ἐν ὑμῖν” (For God is the one working in you). The first observation to be made from this segment should be that Paul chose to put θεὸς at the beginning of the sentence, rather than ὁ ἐνεργῶν. As the latter is the subject (since it has the article), we would normally expect the subject to precede ἐστιν. It should be noted thusly that Paul chose to put θεὸς at the beginning of the sentence to provide weight, “For GOD is the one working in you”. This emphasis on God being the one working in the believer would indeed back up the idea that it is not works-based salvation Paul is speaking of in these passages, rather obedience to God who is already working in us.

The remainder of this detailed analysis will be spent on the second half of verse 13, “καὶ τὸ θέλειν καὶ τὸ ἐνεργεῖν ὑπὲρ τῆς εὐδοκίας.” I leave out the translation for this second half because it can go one of two ways, depending on how the substantive infinitives are translated. Depending on which translation is chosen, the implications of this verse significantly change.

The common translation amongst today’s major translations (ESV, NASB, NIV, KJV) would say something to the effect of “both to will and to work for His good pleasure.” And this makes sense considering the standard use of the infinitive verb. However, as Wallace points out, because the infinitives are used substantively and they have the article, it is entirely possible for a different translation to be rendered. This translation would be something to the effect of “both the willing and the working for his good pleasure.” (Wallace, 602). While the wording only slightly changes, the meaning has a drastic difference. While the former translation only tells us that it is God who is working in the believer, the latter translation would tell us that it was God who both initiated and is currently working in the believer. While I would like to see this verse behind my reformed bias and stick to the latter translation, I see no immediate reason to choose this translation over the one used by every English translation. There appears to be nothing in the passages immediate context nor the letter as a whole to give reason to choose the latter translation.

That being said, the former translation of “both to will and to work for his good pleasure” is plenty of evidence to show that Paul is not speaking of works-based salvation in verse 12. Rather, this segment provides much weight to the idea of grace-fueled obedience. Why should believers work out their salvation with fear and trembling? Because it is GOD, the God of the universe and the head of the Trinity who dwells and works in us, therefore it is necessary for us to be obedient to his working in us to fuel our will and work for His good pleasure.

Bibliography

Aland, Kurt, Matthew Black, Carlo M. Martini et al. The Greek New Testament, Fourth Revised Edition (With Morphology), Php 2:12–13, Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 1993; 2006.

Fee, Gordon D. Vol. 11, Philippians. The IVP New Testament Commentary Series, 11-39. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1999.

Metzger, Bruce Manning and United Bible Societies. A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, Second Edition a Companion Volume to the United Bible Societies’ Greek New Testament (4th Rev. Ed.), 546. London; New York: United Bible Societies, 1994.

Silva, Moisés. Philippians. 2nd ed. Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament, 1–22. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2005.

Wallace, Daniel. Greek Grammar: Beyond the Basics. 46, 602-603. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1996.

Runge, Steven E. High Definition Commentary: Philippians. Bellingham, WA: Logos Bible Software, 2011.

Well, it’s getting to be the end of the semester, and school + life = craziness! While trying to balance so many things, I find myself unable to sit down and write some blog posts for you all to enjoy. I did however recently write a paper for my Greek Exegesis class. As it turns out, I didn’t write complete heresy, so for the next week or so I’ll be dividing excerpts of that paper up into some posts for you all to read. I hope you get something from it! The paper itself was an exegetical paper on Philippians 2:12-13.

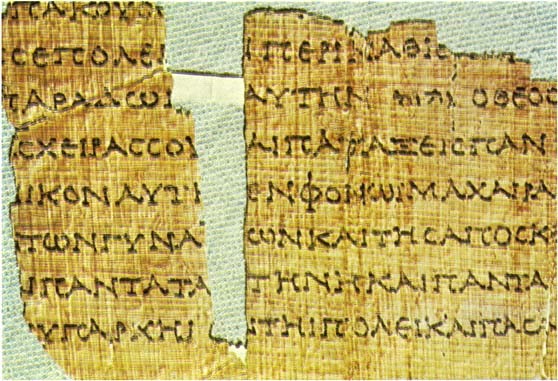

I. Translation

12 Ὥστε, ἀγαπητοί μου, καθὼς πάντοτε ὑπηκούσατε, μὴ ὡς[1] ἐν τῇ παρουσίᾳ μου μόνον ἀλλὰ νῦν πολλῷ μᾶλλον ἐν τῇ ἀπουσίᾳ μου, μετὰ φόβου καὶ τρόμου τὴν ἑαυτῶν σωτηρίαν κατεργάζεσθε· 13 θεὸς γάρ ἐστιν ὁ ἐνεργῶν ἐν ὑμῖν καὶ τὸ θέλειν καὶ τὸ ἐνεργεῖν ὑπὲρ τῆς εὐδοκίας.

12 Therefore, my beloved, just as you always obeyed, not as[2] in my presence only but now much more in my absence, with fear and trembling workout your own salvation. 13 For God is the one working in you, both to will and to work for his good pleasure.

II. Survey of the Text

Paul’s letter to the Philippians is one that is marked by endearing words of cheer, joy and rejoicing. It has many of the characteristics of a “letter of friendship”, and it is clear Paul has a very close relationship with this church (Fee, 13). Because of the language and tone associated with the letter, readers often mistakenly believe the Philippian church is one without struggles or problems taking place within the church. However, as exegetes and students of the word we must ask ourselves why Paul felt it was important to use this language and structure in the first place. Upon a closer study of the text, it is clear that there are two underlying situations as the cause for this letter; hardships and suffering within the church, as well as enemies and external opposition to the church. It is Paul’s primary goal to provide exhortations against these trials all while having joy in Christ.

Paul immediately begins his letter with an expression of thankfulness toward the Philippian church. It is clear the church is special to Paul, as it was not only his first plant but also the only one to offer up support for his ministry (4:15). It was important for Paul to establish this connection and relationship between himself and the church, as he continues the letter by summarizing his current imprisonment. When the church might be expecting to hear of Paul’s sorrow, he instead speaks of his joy in Christ and the advance of the gospel that has taken place because of his time in prison. Not only do we see Paul using himself as an example in these verses, but we also get our first glimpse of the external opposition facing Paul and the Philippian church (vs. 1:15, 17).

This summary of his imprisonment is Paul’s way of showing an example of what it means to have joy during suffering. He encourages the church to stand firm in one spirit, to be striving side by side for the faith of the gospel, and not to be frightened by their opponents. The important thing to realize about this language is that in order to stand firm, there must be something to stand firm against. It could be debated to the degree to which opposition and weak faith is impacting the congregation, but it is clear in these verses (1:27-30) that the church is facing opposition of some kind. The church itself is engaged in the same conflict as Paul, which is a gift from Christ (vs. 29).

As if Paul’s example of joy during suffering were not a big enough statement, he continues to use Christ’s example of humility to the point of death as means of encouragement and a basis for sanctification in the church (vs. 2:1-11). As it was Christ who humbled himself to the point of death on a tree, counting us as more significant than himself, so too then should we count others more significant than ourselves (these verses are especially relevant as they immediately precede verses 12 and 13, which will continue to be explored in remainder of this paper). With Paul’s preceding example and exhortation to stand firm in conflict (vs. 30), as well as Christ’s example as a means of showing how to treat one another, it is clear that some sort of internal doubt (possibly departures from the faith, see vs. 3:18) and/or external opposition are facing this church.

As the letter continues, it becomes more evident that polemical charges are being placed upon false teacher and opposition facing the church. While not as polemical as the Judaizers facing Galatia or the false teachers Timothy would later face in Ephesus, it is clear by such language as “dogs”, “evildoers” (3:2) and “enemies of the cross of Christ” (3:18) that this group (or groups) were causing some serious issues in Philippi. They appear to place confidence in the flesh – that is worldly status and esteem – things Paul calls “rubbish”.

Upon a closer look at Philippians, we gain a backdrop for how we should read Paul’s numerous exhortations to joy and rejoicing in this letter. It is evident that there is some form of doubt or temptation from within the church, as well as an external group of people opposing the congregation. Despite these circumstances, Paul provides himself – and more importantly Christ Jesus – as examples for rejoicing during suffering. Indeed, Paul commands the church to “Rejoice in the Lord always” (vs. 4:4)!

III. Historical, Literary, Redemptive-Historical Contexts

As is the task of any good exegete, it is necessary for us to take into consideration the historical elements which bear weight on this letter, elements of the literature which might impact our interpretation, as well as the greater redemptive-historical impacts this letter makes on the rest of the Scriptures.

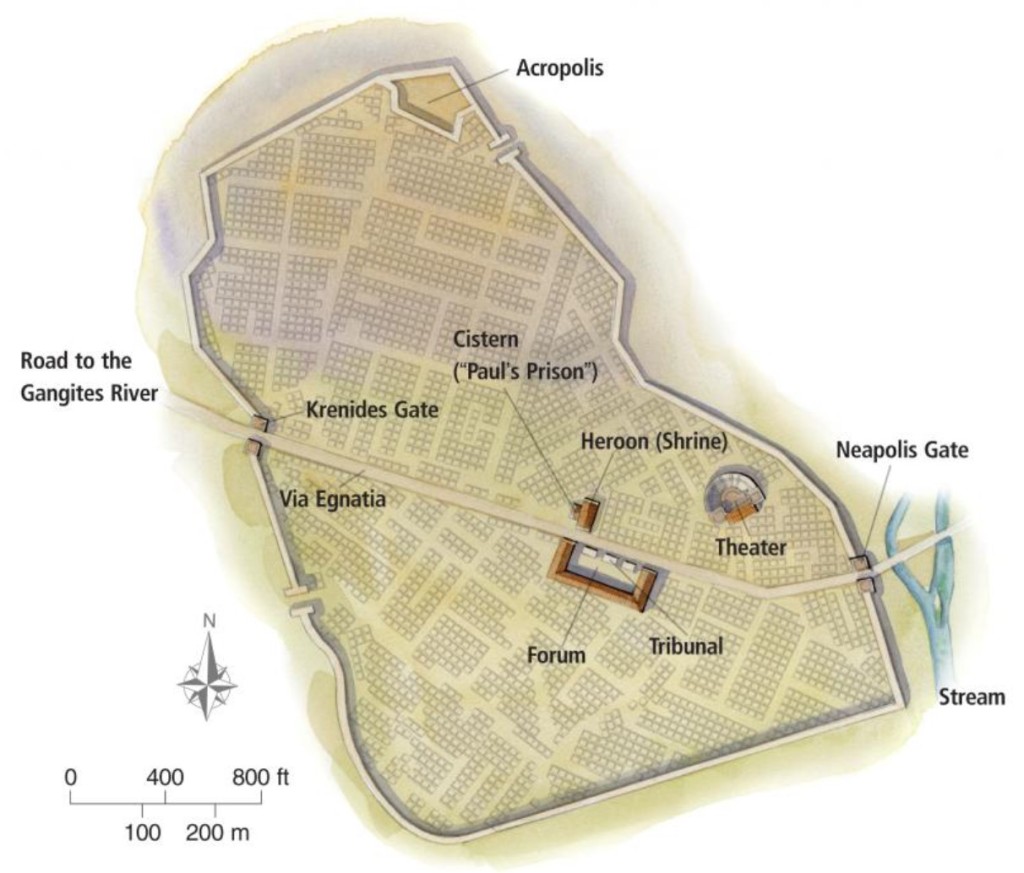

The relationship between Paul and the church at Philippi has significant impact on this letter. While we might think that Philippi was merely another church plant, it is clear even from the text in verses 1:5 and 4:15 that Paul and the church have a close relationship. Moises Silva astutely reconstructs the events of Paul’s ministry, showing that Philippi was Paul’s first plant as well as the first church to faithfully and continually support his ministry (Silva, 2). Indeed, even when the church was unable to help Paul due to their own circumstances, they felt a responsibility to provide assistance to him.

In addition to the relationship Paul has with the church, it is important for us to see the relationship his co-laborers Epaphroditus and Timothy had with the church as well (verses 2:19-30). This not only explains the predicament Paul mentions in chapter 2, but also shows us that Paul’s ministry had multiple occasions and trips to the church at Philippi, either through Epaphroditus, Timothy or Paul himself (Silva, 4, 5-7). Studying the relationship Paul’s ministry had with the church at Philippi serves to put into context the overflowing love and joy Paul has for this church.

While many scholars debate the importance of where this letter was written from, I remain unconvinced that this is significant to our understanding of the letter (I do however agree with Silva and Fee’s apparent dismissal of theories other than the Rome origin). What I believe is more important to our comprehension of Philippians is the categorization of the opposition facing Paul and the church at Philippi. For brevity’s sake I will merely make mention of verse 3:2 as reason to believe that there was a hyper-Jewish Christian sect arising near Philippi. It is ambiguous whether this is the same group taking advantage of Paul’s imprisonment in chapter 1 (Silva, 9).

The style of literature this letter takes on is also important for us to consider. Gordon Fee tells us that this is a letter of two different kinds; a “letter of friendship” and a letter of “moral exhortation” (Fee, 13-20). We are able to classify this letter as such using even ancient literature that have been passed down from this time period, those of Demetrius and Libanius. Fee categorizes the letter as “friendly” because it contains common elements of the friendly letter – the separation between friends (1:27, 2:12), concern for the affairs of both sender and recipient (1:12, 27, 2:19, 34), and that the recipient “does well” to look after the needs of the sender (4:14) (Fee, 13-14). We also see elements of moral exhortation, which are that the writer is the recipients friend and/or moral superior, and that the writer aims and persuasion or dissuasion. Philippians contains large hortatory sections which fit into these descriptions, namely 1:27-2:18 and 3:1-4:3. Considering Paul’s “all of us…should” language, one of the aims of Paul’s letter does indeed seem to be a persuasion towards a certain kind of behavior (Fee, 18-19).

It is also worthwhile for us to study Paul’s use of the Old Testament in this letter. While Paul would normally issue his argument from an extensive use and quotation of the Old Testament, these qualities are missing from this letter (Fee, 22). What we see instead is sort of an inter-weaving of Old Testament into Paul’s written context, otherwise known as “intertextuality”. This style of writing assumes that the hearers will know the original text intimately and that they will understand how it is newly being used. Fee argues that this type of usage is not the type of polemics we might find in Galatians or 1 Timothy, but instead is a writing mutuality and common ground (Fee, 23). An example of this intertextuality can be seen in verse 2:12 when Paul instructs believers to work out their salvation with “fear and trembling”. This language is exclusively used by Paul in the New Testament, and harkens back to language from the Old Testament. It primarily is identified with the fear pagans felt before God because of the wonders he worked for His people (Isaiah 19:16, Deuteronomy 2:25) (Fee, 105).

Finally we must examine the themes of Philippians and how they fit into the entirety of redemptive history. As it has already been addressed, the theme of joy amidst suffering and trial is one of, if not the primary theme of this letter. It is important for us to consider this text in light of a world post-crucifixion, where a church has already been established and is thriving. As a body of believers, what then should the expectation be for the Christian life? Paul could not be clearer than he is in 1:29, “For it has been granted to you that for the sake of Christ you should not only believe in him but also suffer for his sake[3]”. As he will later say in 3:15, “Let those of us who are mature think this way”. The expectation for a believer in Christ following his death and resurrection should be to suffer for his sake, yet in the midst of this to “Rejoice in the Lord always”. This theme in Philippians is especially important for us to grasp onto as servants of God’s redemptive plan as we take his gospel to all peoples.

[1] The UBS Critical apparatus notes that ὡς may or may not be in the original. However, in Bruce Metzgers Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament he concludes that its absence from certain documents is likely accidental, and the presence of the word in p46 as well as in the Alexandrian and Western texts gives strong to support to it being in the original document. I see no reason to disagree with his analysis.

[2] See note above.

[3] The Holy Bible: English Standard Version (Wheaton: Standard Bible Society, 2001), Php 1:29.

Well, finishing this little mini-series took a lot longer than expected. Needless to say that getting engaged, work, school and life are enough to keep me away from writing!

I’ve previously written two entries about the study of Biblical languages, part 1 and part 2. In the first entry I talked about why it is important for ministry leaders, particularly pastors, to have a working knowledge of the original text. In the second entry, I focused mainly on some small but common examples of how to defend the text against common attacks. In this last entry of this series, I am going to discuss a few examples of how the original text can greatly enhance teaching from a given text.

It is rarely the case that a reading of the original language will significantly alter the message of the translation. That should be of great comfort to many, as it shows that our English translations (and others) are mostly accurate concerning the original text. What we do often find, however, is that the message can be significantly enhanced by really understanding the language of the author.

Below I have listed a few examples that I will do my best to explain. I would like to again remind the reader that I am in no way claiming to be an expert on this subject, as I am barely scratching the surface myself. I do however love to share what I am learning with others, and I hope in some way these little examples are enriching to you.

Example #1: Understanding the Original Word

This little diddy was something I discovered in my studies of 1 Timothy a couple of weeks ago. As I was translating and studying 1 Timothy 2:1-6, I was curious at the following line: For there is one God, and there is one mediator between God and men, the man Christ Jesus, who gave himself as a ransom for all, which is the testimony given at the proper time (1 Ti 2:5–6, ESV). My attention was drawn to the word ransom, ἀντίλυτρον in the Greek. Recognizing this as a compound word, I looked up λυτρον in the lexicon to find that λυτρον by itself meant “ransom”. So why the need to compound ἀντί ? Turning to my handy Daniel Wallace grammar to see what he had to say about this, indeed our little preposition ἀντί provides great emphasis to this passage. As it turns out, ἀντί carries the meaning of “exchange”, “substitution” or “in place of”.

Now the passage in the English already says “ransom for all”, so the idea of Christ paying our penalty is already at work here. However, taking into consideration the full word ἀντίλυτρον, we can now really see a substitutionary ransom is what Paul really had in mind here. Paul really wants to get the message across to his audience that Christ’s death was in place of sinners. How sweet this truth is!

Example #2: The Present Progressive

The book of 1 John is awesome because you need very little vocabulary to translate it. It is so repetitive that by the end of the book you feel like an absolute pro who could translate any book in the New Testament. If only this was the case…

1 John 3:9 presents us with an interesting little passage. It reads: No one born of God makes a practice of sinning, for God’s seed abides in him, and he cannot keep on sinning because he has been born of God ( 1 Jn 3:9, ESV). Now from what we know about the entirety of the New Testament, there can be no way this passage means that if you sin once you aren’t a Christian anymore. That isn’t how grace works. But don’t we sometimes think that? Maybe when we’re feeling low, having a week where we’ve really fallen into sin, we start thinking those thoughts don’t we? There are some preachers out there (albeit false ones) who want to lord over you by preaching a perfectionist message, maybe they’re right?

This is where our understanding of the present progressive tense comes into play. The present progressive tense is one that means it is an action that is occurring now and is continuing on into the future. When we read the verbs “makes a practice of” and “sinning”, what we’d find in the Greek language is this is in the present progressive tense. So what we’re talking about here is someone who sins now and continues habitually to practice that sin without remorse. While this is again understandable from our English translations, it is entirely possible for people to get caught up on verses like this.

**As I write example #3, I realize it is worth briefly mentioning Hebrews 2:17, …to make propitiation for the sins of the people (Heb 2:17b, ESV). It is interesting to note that the verb “to make propitiation”, ἱλάσκεσθαι, is also in the present progressive tense. What we can gather from this is that this passage is not referring to a single act of atonement on the cross, but a continual subsequent activity by which Christ continually applies the propitiatory power of His sacrifice (Vos, Redemptive History and Biblical Interpretation, 145). Since this could be an entirely separate post to examine this, for brevity’s sake I will end this note here.

Example #3: The Perfect Tense

The second temptation of Christ (Mt. 4:5–7). Relief, Cathedral of St. Lazarus, Autun, France, 12th century AD.

The perfect tense is a verb tense in the Greek language that is really hard to communicate in the English. The reason for this is the lengthy implications the perfect tense has. The perfect tense can simply be defined by an action that was completed in the past and has results or impact in the present time. An example of this idea would be like saying “I have freed him from jail”, with the present result being that he is still freed. Since it is hard to realize when such a tense is being read in our English translations, we often breeze right through the words without stopping and asking “Well what is the result that action had on present reality?”

The perfect tense is littered throughout the Greek text, and it often can greatly enhance ones message when properly understood. A great example of this can be seen in Hebrews 2:18, For because he himself has suffered when tempted, he is able to help those who are being tempted (Heb 2:18, ESV). The verb for “has suffered” is in the perfect tense, which tells us that Christ’s sufferings are something that happened in the past, but have a result in present reality. The sufferings and temptation that Christ has behind him, and still carries with him as a past experience, enables him to relate and know exactly to what weight and force we are struggling in our temptations.

This message brings such joy and comfort to my soul. The God of the Bible is such a drastically different God than any other man-made god throughout history – he understands what we are going through and sympathizes with us in our weaknesses. I know when I am feeling tempted and shamed in my sinful state that Christ hears me and sympathizes with me, knowing what I am going through.

Example #4: Word Order

Those silly Greeks didn’t quite understand proper word order yet (proper by my American English standards!), so ancient Greek writings can largely put the words in any order the author so chooses. One of the benefits of this is that the author can place certain words before others if he really wanted to provide an emphasis on a word or concept.

Philippians 2:13 has a really great example of this. The beginning of this verse reads, for it is God who works in you (Phil 2:13a, ESV). The Greek for this reads θεὸς γάρ ἐστιν ὁ ἐνεργῶν ἐν ὑμῖν, woodenly translated for God is the one working in you. What is interesting about this sentence fragment is the word order – under normal circumstances we would expect ὁ ἐνεργῶν (the one working) to have been the first two words in the construct, as it is the subject of this clause. However, what we find is that Paul chose to put θεὸς (God) first. This is important for us because it tells us that Paul really wanted to emphasize GOD as the one who works in us. That is the concept Paul wants us to take away, that it is not us who works for him but it is GOD who works in us. This is also especially important if we consider the previous verse, which has often led people to think Paul was teaching a works-based salvation. This is not the case, instead Paul is speaking of an obedience to God already working in us.

—–

Well, that concludes this short series on the importance of language studies. I hope these few examples were enriching to you in some way, and if you are not familiar with languages, you can begin to see how small things here and there can really begin to enhance the message of a passage when the original text is really studied.

Of course there are examples where varying translations can occur from the Greek that might have significant differences in the meaning of the passage (Philippians 2:13, substantive infinitives anyone?). However, I do not think examining such passages would be particularly fruitful at this time, but I may write about them in the future.

If you are familiar with languages, or have had some training in the past but have now neglected to keep up with your understanding of the languages, I hope this series was an encouragement and challenge for you to get your grammars and books back out. For people new to the idea of studying languages, I hope this series has given you an appreciation for the depth that can be found in language study.

When I began this series weeks ago, I set out to answer the question “Why study the original languages if we have modern translations?” Hopefully this served its purpose!