I’ve reached the point in my ministry where I consider myself a seasoned veteran of pastoral internships. Although I start my first pastorate in a little less than a month, the path I’ve taken to get there has exposed me to many different churches across multiple denominations. See, I’ve served in four churches now in the same number of years – both in pseudo as well as formal internships. This has not been by choice. Intense church conflict and poor leadership – in combination with my own sin and prideful ambition – has led me through the revolving doors of many churches.

While it would be easy to wax cynical and bitter about the whole experience, there is something to be said about the lessons the Lord has taught me through it all. Sometimes the best lessons are learned from the hardest circumstances. As I’ve sat under the ministry of multiple pastors and served multiple congregations, I’ve been exposed to both the best and worst ways to handle pastoral interns. In the process, God has helped me capture a vision for pastoral internships that I now hope to employ in my future ministry.

Let me be clear about something from the start: a veteran pastoral intern I may be, but green to the whole of pastoral ministry I still am. The goal of this article is not to sound off pompously as if I have all the answers to a broken system. My goal is to share what has worked and what has not worked in my experience, as well as provide a voice into an often neglected area of ministry in our churches.

It has become evident to me that when it comes to pastoral internships we are facing a systemic crisis. Poorly trained pastoral interns leads to poorly trained pastors. I’ve seen it and experienced it firsthand. On the whole, young men are simply not being shepherded to become pastors today. And I can tell you this much – it would be difficult to find a Christian who is more discouraged than a young man in a bad pastoral internship. I regularly talk with other young men from the local seminary who have given up a career in order to be trained as a pastor. They’re trying to lead their families through financial strain, complete seminary, and find opportunity to serve others with their gifts. But rather than being blessed by the churches they serve, they’re forgotten. They’re given few – if any – opportunities. They’re uncared for by the church and its members. They receive the brunt of Christian cynicism from those who have been hurt by shepherds in the past. “You won’t be ready for a long time,” they’re told, not because of any flaw of their own but simply because these sheep harbor deep wounds. The result is a heap of young men who consistently doubt their calling, doubt their gifts, and are lost in a slough of despond.

I think there are a handful of reasons for the present crisis facing pastoral internships in churches today. First, this is a generational problem. Young men are not being shepherded to be shepherds because their shepherds were never shepherded to be shepherds (say that 10 times fast). Much like a family with generational sin, God gives us the opportunity to pursue a new direction of life and good fruit rather than living under the burden of failure and sin from our past. But such a change requires intentionality. This crisis will never be abated unless a generation of pastors becomes intentional about changing the course of pastoral internships in their churches (Gen-X and older millennial pastors, I’m looking at you). If we don’t do something now, this crisis will persist into the next generation.

Second, pastoral internships aren’t flashy. They’re not sexy. And we evangelicals love flash. We devote our best resources and time to the things we think are most important, and we do it with style. We write large checks to the best speakers to ensure high attendance at big events with the best musicians and modern stage décor. If we survey the bulk of these events that are tailored specifically for ministry training, what will we find? Plenty of conferences and seminars for church planting and missionaries to be sure. Both of which are extremely important, and I want that training to continue. But underneath the excitement of church planting and missionary work, pastoral interns are often forgotten. Yet there may be nothing more important to ensuring the fruitfulness of the church in the future than by investing today in the pastors of tomorrow. Where are the conferences for young pastoral interns? Where are the seminars training pastors to mentor and shepherd future pastors? They don’t exist, because we don’t think it is all that important of a work.

Third, many pastors are too busy trying to build their own platform. Let’s just be honest here for a second: every shepherd with a pulpit struggles with a temptation to make a name for himself. This is especially true in the age of celebrity pastors with blogs and podcasts. While I often talk to young men who have been told things like, “The church isn’t ready yet,” or “I’m not ready to train you yet,” or “There isn’t enough opportunity yet,” the reality is these pastors are more concerned with their platform and the success of their one church than the future of Christ’s church. A vision for pastoral internships is born out of a Kingdom vision that desires to see more healthy churches that are led by healthy shepherds. More healthy churches means more healthy church planters and missionaries. More healthy pastors means more healthy sheep with Kingdom values and virtues shaping the world around us.

Fourth, church members haven’t been taught to know why this work is important. If pastors aren’t investing in future pastors, then the members certainly won’t either. One of the reasons I hear most often for why churches aren’t investing in interns is because they don’t have the resources for it. Now, I understand that there are exceptional circumstances with churches that are nearly closing their doors and are pinching every penny they can. But generally speaking, if pastors sold a robust vision for pastoral internships to the members, I think they would buy in. Remember, we devote our best resources and time to the things we think are most important. Or, in Augustine-speak, we devote our resources to what we love most. If your people love Christ’s church and want to see it grow into the future, they’ll invest in interns.

At the root of each of these reasons – and the several others not listed here – is the fact that we’ve simply forgotten the importance of pastoral internships. My pastor – who I believe has caught the vision – often reminds our church that if we don’t invest in young pastors now, then there won’t be any good pastors around to shepherd his grandchildren. Yet somehow we’ve forgotten that one day these young men in our care will be the undershepherds of God’s people. We’ve forgotten that they will be judged with greater strictness (James 3:1), and that they must be able to rightly handle God’s word (2 Tim. 2:15). These young men need to grow and mature in such a way that all may see their progress (1 Tim. 4:15). This requires more than just a formal education, it also requires learning how to love people well. It requires learning how to be holy. This kind of training needs to come from pastors who know how to train young men to do all this well.

What we need is a big, robust vision of pastoral internships that is worthy of the high calling which Christ has given to his church. We need a vision that seeks to display the glory of God through the proclamation of the gospel and the building of the church into the next generation. I don’t know what that will look like for you and your church, nor do I want to pretend that I have all the answers. However, I do want to offer several pieces of advice for you and your church as you seek to invest in your interns. My hope is it will at least start a conversation for you, your elders and your members. Maybe it will even help you create a beautiful vision for interns in your congregation.

- Create an internship description. Nearly all of the problems I hear and see with interns involve miscommunication and expectations that don’t align. Treat the internship like a real vocation with real goals, objectives, expectations, and ways to be evaluated. This is going to save you and the intern a lot of heartache and stress in the future.

- Get excited about it. If you’re excited about what God might do through the training of future pastors, your people will feel it. They’ll get excited too. Talk about it at congregational meetings. In the weeks leading up to the intern starting at the church, use time in your announcements to talk about it with your people. Scheme and dream with your elders about the opportunities you could provide to a future pastor in Christ’s church.

- Get an intern. This sounds obvious, but it all starts here. And remember, there are a lot of teaching opportunities that present itself when a church brings on an intern. It serves as a chance for you to teach your people that Christ’s church is bigger than your congregation, and that it extends from generation to generation. It allows you to teach your people (and remind yourself) what exactly a pastor/elder is and how the church is supposed to function.

- Don’t take on more interns than you or the church can handle. I’ve seen many churches – with good intention – take on more interns than the church is ready for. Remember, it is your responsibility to invest in, mentor, and provide feedback for each intern. Don’t take on more interns than you’re able to invest in and observe. If you can’t provide personal feedback for much of the interns work, then you’re spread too thin. If your interns are only getting one or two opportunities to preach per year because the opportunities are spread across 5 interns, you might have too many – even though you have good intentions.

- Affirm the gifts and calling of the intern. For whatever reason, many pastors treat the pastoral calling as a high bar to be reached, rather than a gracious calling that Christ bestows on unqualified men. Rather than holding out affirmation from young men until they meet your personal standards, affirm them quickly and often. It is between them and the Lord to make their calling sure; it is on you to remind them of God’s grace in the midst of doubt, to affirm their gifts when they feel giftless, to remind them that the reason why they’re an intern at all is because you believe they’re called by God to the ministry. One of the best ways to do this is from the pulpit. When you affirm the gifts and calling of your intern(s), the members will start to do the same. It will also help create a church culture that isn’t focused on you alone as the pastor.

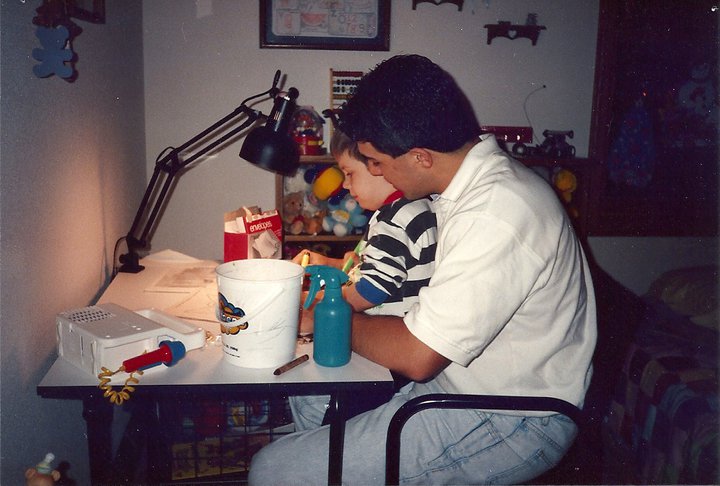

- Be generous with encouragement. Interns will make mistakes. They will doubt themselves. They will be discouraged. Strengthen their souls with your speech. Even if their first sermon is a train wreck, start your feedback with as much encouragement as you can muster. Just as a son wants nothing more than to hear his father say, “I’m proud of you,” so too does an intern want to hear the same from his mentor.

- Spare them your cynicism. After enough sheep attacks, messy pastoral counseling, personal failures, and being sinned against – pastors start to nurse a bitter bone in their spirit. Try to spare your intern from the bitterness of your wounds. They don’t need to be cynical before their first pastorate even starts. Instead, remind them of all the privileges of frontline pastoral ministry and what we get to witness: the joy of new birth, seeing nominal Christians take Jesus seriously for the first time in their life, sin defeated, wounds healed, relationships restored. This will create a steady reservoir for your intern to draw on when they start encountering the mess of ministry, and it will nourish your bitter soul as you are reminded of what the Lord has done through your ministry.

- Use their gifts – don’t leave them on the bench. If we take the Apostle Paul at his word, then the church is one body with many members. Each member has gifts and a unique role to play in the church (1 Cor. 12:12ff). Any ministry philosophy which says that the gifts of some members are less important (or unimportant) is defunct. And yet, so many pastoral interns are given excuses for why they can’t serve. They’re left on the bench. I was told repeatedly that I wasn’t needed because “the church doesn’t need interns.” Can the pastor say to the intern, “We have no need of you?” No, but by casting the intern to the side that is the message they’re being given. Take risks for the sake of building the intern. Let them stutter through a Call to Worship. Let them say something in a sermon that you might have to correct. Let them run with a new ministry idea and see what happens.

- Treat it like a teaching hospital. The best analogy I’ve ever heard for pastoral internships is that the church should be like a teaching hospital. A teaching hospital is a place where young medical students can observe professionals and be mentored under close supervision. The patient may get pricked a few extra times before the student finds the vein, but how else will we have well-trained doctors? The church should be a teaching hospital for pastors. This appears to be the biblical model, for every time Jesus or any of the Apostles rolled into town, they had their whole crew behind them. It was the expectation that when Paul showed up that Timothy, Lucius, Jason, Tertius, and the whole gang would be there. Why? Because they were apprenticing under Paul to eventually take up the work of a ministry leader. So, bring your intern everywhere that you can. Give your members the expectation that when you show up, the intern will probably be there too. Let them know they might get pricked a few extra times while the intern makes mistakes. Bring him to elders meetings and counseling sessions. Let him into your sermon writing process. As time goes on, let him begin to do the work. Let him speak up during counseling sessions while you observe him. Let him share his opinions in elders meetings. Provide him detailed feedback with his strengths and weaknesses.

- Pay them. I get it, money is tight. But as I’ve said repeatedly, our spending reflects what we believe is important. And if this is one of the most important tasks of the church, then we’ll back that up with finances. The intern may not be ordained yet, but they’re still doing the work of the ministry. In most cases, they’re working 20-40 hours for the church rather than working 20-40 hours for a different job. We should try to pay them as such. Being a 20- or 30-something intern is already humiliating enough, but being a 20- or 30-something unpaid intern that can’t provide for his family is even worse. And we can be (more) creative about this. Take up a special offering a few times a year, or set aside a special giving fund in the church. Even if 10 members gave an extra $25 a month toward the intern fund, that is still a few weeks of groceries for the intern and his family each month. Encourage your members to be on a weekly meal rotation for the intern. Help them find cheap housing from a member within the church. There are plenty of ways to provide for interns, even if a salary isn’t one of them.

- Send them. A successful internship ends by sending the intern out to their own pastorate. In rare circumstances the church will have the funds to bring on its intern, but this is rare and should not be the ultimate goal. If getting a job at your church is the ultimate goal, then the scope of the internship will be narrow and will by its very nature be inward focused (the needs of our church) rather than outward focused (the needs of Christ’s church).

Pastors, one of the most important tasks before you is to build a gospel legacy into the next generation. You have nothing to lose and everything to gain by capturing a God-glorifying vision of pastoral internships for your people. If you don’t stand up now for the future generations of the church, who will?

Have you ever been frustrated at the prevalent disregard Americans show toward experts in fields that laypeople otherwise know nothing about? Joe Average who thinks he knows as much about the political system as the most educated person on Capitol Hill, Betty Bologna who refuses to listen to anyone on a subject now that she has read one blog post about it, or Conspiracy Corey who posts 15 obscure Facebook links a day from random corners of the internet – sure that he’s discovered the secret nobody else knows?

Well, Tom Nichols became frustrated enough that he wrote a book about it. The Death of Expertise is an important book which tries to tackle the issue of not only of why Americans can’t seem to dialogue anymore, but why we actually despise those who have expertise in fields that we do not. The argument is relatively simple: we don’t respect people who have more expertise than us anymore. As Nichols says it, “Americans now believe that having equal rights in a political system also means that each person’s opinion about anything must be equal to anyone else’s (p. 5).” Despite all of the advancements we have made as a society, “the result has not been a greater respect for knowledge, but the growth of an irrational conviction among Americans that everyone is as smart as everyone else…we now live in a society where the acquisition of even a little learning is the endpoint, rather than the beginning, of education. And this is a dangerous thing (p. 7).”

I agree. And as I set out to read the book, I couldn’t help but be struck at how accurately Nichols describes the predicament of American churches and Christians. There is an increasingly nasty disposition American Christians have toward one another, especially those who claim (rightly) a better understanding of the faith than they do. This is not only true of lay Christians toward pastors, leaders and scholars, but it is true between lay people themselves. The older and wiser saint no longer carries the respect of the youth which Scripture says is good and necessary for the health of the church (Leviticus 19:32, 1 Timothy 5:1-2, etc.). Trained leaders are despised for their instruction, rather than being honored for the position and charge God has given them (1 Thessalonians 5:12-13, 1 Timothy 5:17-18, etc.)

One section of Death in particular has struck me in how much it applies to the state of the American Church, and that is the chapter on American higher education. It is in this chapter that Nichols attributes much of the “death of expertise” in America to the higher education system. As I read this chapter, I couldn’t help but find parallel after parallel between the problems besetting higher education and the American Church. I want to focus on three for the remainder of this post: The Sold Experience, Over Saturation, and Over Inflation.

- The Sold Experience

Although higher education was originally a place for the select few privileged people who could both afford the tuition and compete academically for their place in the school, “today attendance at postsecondary institutions is a mass experience (p. 71).” It is now the expectation that most people will – and everybody should attend college. Whereas obtaining a college degree once separated those with educational achievement from those without, this is no longer the case. The reality is however, that not everyone can or should make the cut to attend a college or university. But as higher education has become a product for the masses, it no longer guarantees a “college education” but instead a full-time experience of “going to college” (p. 72).

In other words, there is an increasing commodification of education. Students are not treated as such but instead are treated as clients. Those schools which know that they can’t compete for the highest tier of students instead focus on giving people what they want: a four-year getaway complete with apartment-style housing, state of the art recreation centers and Four-Star dining.

With remarkable similarities in many so-called churches in America, Christianity is no longer a system of beliefs and truths to know and be internalized but instead it has become an experience to share with others. Those churches which do not trust in the God-given means of conversion and growth (the preached Word, Sacraments) instead turn to selling an experience to attract the masses.

I recently went to the website of one very popular mega-church in my area to see what they believed and taught. It was extremely difficult to find a page that lists the church’s beliefs, and when I could, it was so generic and ambiguous that I could hardly distinguish it from a self-help center. Instead, the main page flooded me with information about their live-streaming services and the friendly, convenient experience I could have from the comforts of my own home. The “About Us” page contained testimonials – dare I say user testimonials – about how their life had changed since they bought the experience the church had sold them. I wasn’t quite sure if I was on a church website or something for essential oils (these days it seems like it could be one and the same).

Or consider the pamphlet I found in my mailbox for another local “church” which offered me a free week pass for my kids to attend their amazing indoor playground and recreation center. If I would just attend their church, my kids would have so much FUN while I would be ENERGIZED by the experience I’ll have. What does the church actually believe? Who knows, but at least I’ll have fun, right?

While these stories are anecdotal, we all know that these kinds of examples aren’t hard to find. When congregants become consumers, the Christianity they drink from is a watered-down and tasteless variant. The difficult task of confessional and Bible-teaching churches is to convince these people that even though they’ve shared in some generic barely-Christian experience, they haven’t yet tasted the real thing. This is often harder to do than just giving people the real thing in the first place.

Tell such a person that what they’ve bought into is unhealthy – often not even Christian – and the response is one grounded in experience and not Scripture. “My faith has grown tremendously through this, doesn’t that matter? People come into the faith through this, so who are you to say it’s wrong?” Well, if by faith you mean an ambiguous pseudo-Christian experience that they now sort of share with you, then I suppose you’re right. But if you mean an acceptance of the truths of the Triune God, the historic work of Jesus Christ on our behalf, the depths of our sins, and an application of Christ’s benefits to us – then I’m afraid you’d be terribly wrong.

After all, none of these things matter so long as you’ve bought into the shared experience of the “Christian” product of the masses.

- Over Saturation

If you can’t win people with their need for a robust and intense education, then you can certainly win them with a four-year getaway with their friends. If you can’t win people by preaching and singing the truths of the Scriptures every week, then you can certainly win them by promising they’ll have fun. Most of the time.

However, as the experience is bought up by the masses then the population becomes saturated with people who think they’ve obtained something they actually have not. Nichols points out how small state colleges and schools try to sell students into believing they’re paying for something that is actually a higher-tier product. They offer degree programs that they really aren’t qualified to teach – not only at the undergraduate levels, but at the graduate and doctoral levels as well. The problem here is when underqualified schools offer courses and degree programs as though they are equivalent to their better-known counterparts. Although there is a large quality gap between a competitive university and a “rebranded” smaller school, the student with the lesser-quality degree believes they have actually achieved the same degree as the student from the competitive university. If two students from two different schools have the same degree (even if it is in name only), how could your degree be better than mine? My view and opinion is just as important as yours – we have the same degree…even if my degree was from an unqualified and (perhaps) unaccredited program (p. 92).

The American Christian experience is facing a relatively similar phenomenon. Is every church the same? No. Does every church believe the same things? Not at all. Are all churches as rigorous for their demands from members or the education of their leaders? No. Yet, more and more, just because someone bought into the generic Christian experience they believe their opinion counts just as much as anyone else’s. The person who attends a non-denominational and entertainment-driven church once a month and who barely reads their Bible flaunts their opinion even more strongly than the 65-year-old woman who has attended church every Sunday and has studied the Bible daily under the tutelage of her pastors for generations. The individual who only knows enough out-of-context Scripture from the Gospels to proof text his or her views on social issues knows just as much about Christian ethics as the individual who could outline and quote extensively from numerous books of the Bible. The non-educated and untrained pastor believes their interpretation to be as valid as the pastor with two advanced degrees simply because they share a similar title.

This is absolutely ludicrous, and yet, it makes sense if one judges being Christian not off of beliefs held but an experience that is shared.

- Over Inflation

When college becomes an experience to be sold rather than a degree to be earned and the population becomes saturated with individuals buying up the product, then the business needs to carry to the client. At the university level, this means the student is always right – even when it comes to their grades.

As Nichols points out, as the cost for the college experience goes up, so too does the demand for better grades. Students who graduate with a high GPA no longer reflect their level of education or intellectual achievement. A study of two hundred colleges and universities through 2009 found that A was the most commonly given grade. Grades in the A and B range now account for more than 80 percent of all grades in all subjects. In 2012, the most frequently given grade at Harvard was a straight A. At Yale, more than 60 percent of all grades are either A or A-. High grades are now rewarded not for academic achievement, but simply for course completion (pp. 94-95).

And so, in similar fashion, as the Sunday church service becomes an experience to be sold and the population becomes saturated with individuals who have bought into a shared experience, the business starts to cater to the client. Give the people what they want – fun, entertainment, positivity. Tell people how good they are in a bigger, louder, faster and sleeker fashion. Stay away from the stuff that turns people away – sin, consequences, repentance, and divisive topics.

Fortunately, this is where the similarities end and we find a major difference between the American church and university. Church leaders and pastors may believe they’re able to come up with new and ingenious ways to grow churches and sell the Christian experience, but ultimately all of these means will fail. We may try to do what we think is best to grow numbers and get more people into seats, but ultimately it is God who gives the growth (1 Corinthians 3:5-9). Christ builds his church, not the “wisdom” of man.

So, perhaps, if we want more people to share in the faith which we hold, we should stop selling them some generic notion of a common experience. Instead, let’s give them the full and wonderful truths about our God, about ourselves, and our glorious savior which the Bible so beautifully lays out for us. “For the foolishness of God is wiser than men, and the weakness of God is stronger than men (1 Corinthians 1:25).”

But then again, what do I know? Your opinion is probably just as good as mine.

If you’d like to read this in PDF format, please click here.

My brother will forever be one of my heroes.

Joe Hein was a tireless humanitarian. Skilled in business, he instead spent many of his years relentlessly advocating for the less fortunate. Joe spent some time as a peace-keeper in Bosnia during the crisis there. While he was in the United States, he worked for a senator and strongly advocated for reading programs for underprivileged students in the inner city of Washington D.C. He also worked hard to get similar programs started on Native American Reservations in South Dakota. This was a man who didn’t have much, but emptied his wallet every time he passed a homeless person on the streets. Charming, intelligent, gentle, kind and attractive – Joe Hein was looked up to by others for inspiration and hope.

More importantly, he was the best older brother I ever could’ve asked for. He was 17 years my senior, which meant that he was graduating high school and leaving the house around the time I was born. As far back as I can remember, my brother had something of a “legend” status in my head. When he came home from college, his older brother game was always on point. He taught me how to read a clock, and he encouraged me to read with bribes. He played basketball with me in the driveway, and took me out to train as a skee-ball champion at Chuck E. Cheese. He trained me up in the ways of Dallas Cowboy fandom. He wasn’t afraid to show me physical affection, and he modeled compassion and mercy for me when he took me to serve in homeless shelters with him.

On April 25, 2000, we lost my brother to the monster called depression. Even the strongest and bravest knights can fall to this beast.

Depression has seen increasing awareness in recent years – and for good reason. According to the Anxiety and Depression Association of America, nearly 18% of the U.S. population suffers from some kind of anxiety-depression disorder. Major Depressive Disorder is the leading cause of disability between ages 15 to 44, affecting 15 million people (about 7% of the population). Of course, these are conservative statistics as many who are silently suffering don’t come forward to ask for help.

Yet, despite all of the advancements in awareness and treatment, depression still has something of a stigma in our general culture. It is rarely talked about; and our silence encourages sufferers to persist in silence. Silence perpetuates shame, and shame perpetuates depression. It is a vicious cycle which many people fear they can never escape.

Perhaps part of the problem is we don’t like the fact that depression does not fit neatly into one paradigm. It’s not as simple as positive thinking. Many individuals will still struggle even after receiving years of the best counseling available. While medicine can be of great benefit to some, it can also make symptoms worse. As a Christian, I believe the message of the gospel offers great hope to sufferers of depression. Yet I also know that it’s not as simple as “take two doses of John 3:16 and call me in the morning.” The Bible doesn’t paint the human experience so naively and neither should we.

In fact, I think the Bible gives us much wisdom and insight into better caring for those who suffer from depression. In memory of my brother and – in the hopes that as a result of his death I may be able to help others who suffer as he once did – I want to offer a few pieces of this wisdom to you in the remainder of this article. I remember him say that he used cbd oil for anxiety and his depression every day to improve his mood.

First, the Bible presents us with a robust understanding of the human being. Depression is often met with one of two extreme solutions today. The first is a hyper-physical view of the person: all our problems are either medical issues within the body or originate from not having our physical needs (food, sleep, sex, etc.) met. The second view is a hyper-spiritual one, which centers our problems in our wrong beliefs about ourselves. If we think/feel/believe more positive things about ourselves, our issues (i.e. depression, etc.) will go away.

In the middle of these two extremes is the biblical view of the person. Commonly referred to as the dichotomist view, the Bible presents the human being as both material and immaterial, both a physical and a spiritual being. Some might call us an “embodied soul” – a term I really like. There are many places in Scripture which show this view, but I will just highlight a few of them:

- God made man out of two substances, dust and spirit (Genesis 2:7).

- As Christians, when we die our bodies return to the ground but our spirits return to God (Ecclesiastes 12:7).

- Christ summarizes the person as both body and soul (Matthew 10:28).

-

Paul, in his defense of the resurrection, cannot comprehend of a person without a corporeal nature (1 Corinthians 15:35-49).

What does this mean for us? It means that we should expect suffering like depression to have both physical and spiritual symptoms. It means we need to labor hard to care for the entire person, and not just a part. It means we shouldn’t try to neatly fit out friends into a one-size-fits-all paradigm.

It also means we must distinguish between physical and spiritual symptoms. This is important for two reasons: 1) because we do not want to hold people morally responsible for a physical symptom, and 2) we do not want to excuse spiritual problems or lose hope for spiritual growth when there has been a psychiatric or physical diagnosis. Here are some examples of what it might look like to distinguish between physical and spiritual symptoms for someone who is going through depression.

|

Physical |

Spiritual |

|

Insomnia or hypersomnia |

Shame |

Secondly, the Bible reminds us of the painful realities of life. The world isn’t sunshine and rainbows for anybody. Many of us want a quick solution that will fix our many problems and struggles. Some people will even sell Christianity to you in that way – as if confessing belief in Christ will make all your problems go away.

Yet the Bible doesn’t give us a quick solution, nor does it fool us into believing that following God leads to an easy life. In fact, the greatest heroes of the Christian faith all suffered immense physical and spiritual torment. Moses doubted his call as a prophet and was often chastised or even betrayed by his family and the Israelites. After defeating the prophets of Baal, Elijah retreated into the wilderness by himself (in an episode strangely similar to depression) and wished death upon himself (1 Kings 19:1-18). Jesus was a man of much sorrow (Isaiah 53:3), and after being betrayed and abandoned by his 12 closest friends he cried out to his Father, “My God, My God, why have you forsaken me (Matthew 27:46)?” The Apostle Paul, having faced much suffering, despaired even of life itself (2 Corinthians 1:8).

Why does this matter? Knowing the realities of this life, we are able to have compassion on people in the midst of their suffering and trials. Rather than giving them platitudes which we know won’t help, we can meet them with hope and strength to persevere to the end, even if the darkness never lifts in this life. Which brings me to my last point.

Finally, Christianity offers us real hope. Clearly I don’t mean the kind of hope which says, “Believe this and your depression will go away.” I’ve met many people whose faith has transformed their struggles with depression; I’ve met many people who have still needed years of counseling and medicine to coincide with their Christian faith. So what kind of hope do I mean?

The Bible teaches us that when we confess saving faith in Jesus Christ for the forgiveness of sins, we are adopted into the eternal family of God. Adoption is the height of our privilege as God’s people. This doctrine reminds us that in our salvation we are brought into a family. While we were formerly separate from God and walking in darkness, we are now “called children of God, and so we are” (1 John 3:1). As we become sons and daughters in our vertical relationship to God, we become brothers and sisters in our horizontal relationship to one another.

Our society today wants us to believe that our worth and value is based on our own decisions and merit. Our surround culture says that worth and value are measured by our job performance, our charity and good deeds, or even our sexuality. If we haven’t found our worth in these things, then we need to keep looking until we’re fulfilled. Is it any wonder that depression is on the rise with each passing year? Failing to achieve these standards of worth only sets us up for doubt and disappointment.

In stark contrast, the Christian knows that their worth or merit is not found in themselves, but it is found in the very fact that they belong to a loving Father. Even when we don’t believe it, even when we don’t want to believe it – it’s still true. Once we’re adopted into the family of God we bear his stamp forever upon us, a stamp which reads: loved, valued, precious, beautiful, created with purpose, a child with full access to all the rights and privileges of a son or daughter of God. It’s a bit of a mouthful.

This is a hope that points us away from the things we’ve chosen to give us purpose and define us, and towards the only title which we need to give us purpose: child of God.

When we properly understand what it means to be adopted into the family of God, we know that we can’t abandon our brothers or sisters to face their struggles alone. Because our worth is found not in the things of this world but in the arms of a loving father, there is no effort, no amount of time, no amount of love that is too much for the people of God to give to those in our midst going through any kind of struggle. That is simply what family does; they care for and love one another when all other lights go out.

So, what can you do to help people struggling with depression that you know? I’d like to offer six things:

- Read this article I wrote. This isn’t shameful self-promotion, but I know many people who have been greatly helped by the material in this article. It is a much more in-depth approach to some of what you’ve already read here.

- Pray. Pray for them, pray for your own heart. Pray that God would lift them out of the mire, and give you a greater compassion for their particular kind of suffering – especially if you haven’t struggled with depression yourself.

- Listen. Be Present. Often, bearing each other’s burdens looks less like speaking and simply lending a listening ear and a bodily present. Simple, small reminders go a long way (“You’re not alone”, “I’m here”, “It’s not your fault”).

- Offer your service, not answers. It’s impossible for us to have the answer and solution for someone else’s depression. But, you can offer yourself as an aid during their struggle. Ask them, “What can I do to serve you?”, or “Can I go with you?” (to their counseling sessions, should they be in counseling). Counseling can often be more effective when someone you trust comes with you.

- When the time is right, encourage them with the gospel. Charles Spurgeon once said, “If we suffer, we suffer with Christ; if we rejoice we should rejoice with him. Bodily pain should help us to understand the cross, and mental depression should make us apt scholars at Gethsemane.” Remind our friends who are struggling that our suffering confirms our adoption and status as co-heirs with Christ (Romans 8:17), that we have a savior who knows the pain and struggle that we are going through and meets us in our pain and need.

- Ask the hard questions. Even though it may be difficult or awkward, don’t shy away from the hard questions. “What kind of thoughts are you having?” and “Have you thought about hurting yourself?” are important questions to ask when people are going through depression. If they have thought about bringing themselves physical harm, then it is important to pursue immediate help through their counselor or some other means. Contact your pastor, their counselor or other family that can help during this time.

Finally, if you or someone you know are going through depression at this time, I want to highly recommend this book to you.

There is a temptation when we look back on figures in history to view them as a finished product; individuals who began their life’s journey in as prolific of a manner as the way they ended it. The Reformed tradition often gets this wrong when we look back on figures like John Calvin. We know of his incredible achievements, yet there is another side to John Calvin: a man who suffered much and caused sufferings for others, a man who got as many things wrong as he got right, a man who struggled with the sins of pride and poor temperament. I have learned much from Calvin’s works and his successes, but I’d like to suggest at least four lessons that we can all learn from some of his mistakes and failures in his early years of ministry.[1]

There is a temptation when we look back on figures in history to view them as a finished product; individuals who began their life’s journey in as prolific of a manner as the way they ended it. The Reformed tradition often gets this wrong when we look back on figures like John Calvin. We know of his incredible achievements, yet there is another side to John Calvin: a man who suffered much and caused sufferings for others, a man who got as many things wrong as he got right, a man who struggled with the sins of pride and poor temperament. I have learned much from Calvin’s works and his successes, but I’d like to suggest at least four lessons that we can all learn from some of his mistakes and failures in his early years of ministry.[1]

By 1536 John Calvin had begun his work of ministry in the city of Geneva, Switzerland. He showed much promise in his zeal and understanding of the Scriptures. By 1535 he already had a first edition of The Institutes printed, and it was a complete enigma to everyone how a twenty-five-year-old man who never had formal theological training could write such a magnificent work. Older pastors and Reformers were inclined to take interest in his success and training.

We have letters that were exchanged between at least two of his mentors: Martin Bucer and Simon Grynaeus. In these letters we find a furious and intemperate Calvin who made accusations of his mentors. Bucer’s response to Calvin was firm, and he told Calvin that everything he did was out of love. Calvin understood what Bucer was implying: for all of his theology, Calvin lacked love. Bucer’s rebuke crushed Calvin.

In a similar fashion, Simon Grynaeus wrote to Calvin and rebuked him for his rancid language toward other church leaders. Grynaeus pointed out Calvin’s arrogance, and told him he was too prideful over his education and superior intellect. Between these two men, Calvin was crushed by the weight of his own relational sins. His youth and immaturity brought out his lack of love, his arrogance, and his pride.

Lesson 1: Youth breeds immaturity. Speaking as a person in ministry who hasn’t yet passed the age of thirty, this is a lesson I don’t like to hear. Like Calvin, I have often committed the arrogant sin of making accusations toward older leaders in ministry that were simply a result of me not being able to see the full picture. Certainly no one should be despised for their youth (1 Tim. 4:12). Yet this doesn’t change the fact that youth and inexperience is fertile soil for pride and immaturity. Young Christians would be wise to give the proper weight to the insight and experience of older brothers and sisters in the faith.

Calvin’s pride and arrogance had not yet gotten the best of him. Along with William Farel (another Reformation leader in Geneva), they had entered into a conflict with a council in Berne (the capital of Switzerland) over the minor issue of liturgical rites that should be used in the worship of the church. Calvin soon began denouncing the Bernese Council from the pulpit, calling them the “council of the devil.” He was quickly labeled as a hot-headed troublemaker, especially after he and Farel began refusing communion rites to the whole city of Geneva. The Bernese Council ordered Calvin and Farel to leave the city within three days.

What happened next still astonishes me and breaks my heart. Calvin and Farel headed to Zurich, but stopped in Berne to try and make a deposition while they were there. The two men openly lied to the Council and presented a very tailored account of the conflict, claiming that they had never opposed the Bernese liturgical rites and that a conspiracy had been mounted against them. Calvin’s attempt to win over the Council by openly lying to them backfired, and his reputation was severely damaged.

Lesson 2: Words have the power to destroy. Gossip and envy are the greatest enemies of God’s people. There is no quicker way to tear down unity in the church than with our words. This was clearly the problem in the church James addressed in his epistle, as his rebukes over taming the tongue come just before his admonishment about the envy which was tearing apart the church (James 3:1-4:4). All it takes is saying one thing we shouldn’t have said, and then it is out there forever to wreak havoc on relationships and friendships. In Calvin’s case, his words both publicly and private brought disaster and ruin. Not only did his personal relationships and reputation suffer, but the broader church in Switzerland suffered as well. It is important for Christians to resolve never to speak ill of another, or we too will bring similar consequences on our life and in our churches. Gossip and slander are never worth it.

A synod arose in Zurich made up of the leading Swiss churchmen and reformers. Multiple issues were discussed at this synod, in particular an ongoing dispute with Luther over the Lord’s Supper. Calvin and Farel were also a subject of discussion, and it was to their shame when they realized that they were regarded as the problem in Geneva, not the victims. In the eyes of these leading reformers, they had committed the horrid sin of bringing discord and division to the church.

Lesson 3: Unity and charity have priority over winning an argument. In other words, we want to win people – not arguments. Calvin was learning a lesson that many evangelicals need to learn today: have unity in the majors, and charity in the minors. The way we dispute amongst ourselves about doctrinal disagreements still needs to reflect the kind of love and unity Jesus prayed for in the Garden (John 17:20-26).

By this point, Calvin was beginning to learn all of these lessons too. He had bruised pride and a shattered ego – and it showed. Calvin doubted his calling to serve the church and was hesitant to resume the work again. In one letter to another church leader he wrote, “For though when first I took it up I could discern the calling of God which held me fast and by which I consoled myself, now, on the contrary, I am in fear that I would tempt him if I were to resume so great a burden, which I have already felt so insupportable.” Calvin drifted and felt a loss of purpose or meaning. Over the next three-and-a-half years, he meditated on these lessons he had learned. By the time he returned to Geneva in 1541, he had grown in wisdom and maturity and in many ways became the winsome and pastoral leader we regard him as today.

Lesson 4: Growth doesn’t come without resistance. It’s just as true for us physically as it is spiritually. One of the repeated themes of the Bible is that the Lord uses pain and trial to refine us more into the image of Christ (Hebrews 12:3-17. 1 Peter 1:3-7). When we first become Christians, many of us walk around with a kind of spiritual swagger. Through trial and affliction, the Lord gives us a limp to remind us of our daily need for his grace. Don’t underestimate what God is doing in your difficult season.

[1] Material for this article was taken from Bruce Gordon’s biography, Calvin. Particularly, chapters five and six.