2018 Update: This is a post originally written for the 2016 year. I’m updating it again for the third year. I’ve also included recommendations for a few devotionals to accompany your daily Bible reading, books to help you in your communion with God, as well as a recommendation for a book on productivity in the New Year. I hope this post helps you reach your goals!

And hey, before you get started, can I just be honest? I fell off my plan the past few months. In fact, you could say I’ve been completely undisciplined in this area. Perhaps you find yourself in a similar spot, maybe even ashamed because you couldn’t stick to your 2017 goal. The good news is, there is grace for us when we fail; grace that picks us up to keep going. Our Father is not ashamed of you for trying – and you shouldn’t be either.

I want to persuade you to start a personal Bible reading plan for 2018. But first, a personal anecdote.

I used to be one of those people who scoffed at the concept of Bible reading plans. All of these books and calendars that aim to help Christians read through the Bible in a certain length of time just seemed too “restrictive” to me. I had convinced myself that whenever I read the Bible, it needed to be something I felt like doing. Besides, if I try to read through the Bible in a year, how could I possibly study every intricate detail of each passage that I read? Instead, I told myself that it was better to study one book in depth at a time, so that I could learn it like the back of my hand.

Unfortunately, my excuses were just my own spiritual blindness and hard-heartedness. Between having convinced myself that Bible reading needed to come from the motivation of my emotion and feelings, combined with the fact that I wanted to read extremely slowly (and focus more on a commentary than the Biblical text itself) – the end result was that I read very little Bible. So little, in fact, that it wasn’t until recently that I actually read through the entire Bible.

Can you relate to making excuses as it pertains to reading your Bible? What excuses do you make? Does your job get in the way? Your kids? Is there “just not enough time in the day”? We all do it. My goal here is not to get you to feel down on yourself, but instead I want to encourage you by providing some practical reasons why you should use a Bible reading plan, as well as give you some practical helps on how to do this in 2018. Continue Reading

How are we today as the Church meant to read the creation account as told in Genesis 1 and 2? Many Evangelical leaders today paint the picture that the only faithful interpretations of these chapters are an explicitly “literal” one, meaning that Christians must believe in a young earth, creationist science, etc. One only needs to briefly read and listen to the likes of Ken Ham and Ray Comfort to see how their teachings have permeated into many modern churches and pastors. Such leaders would have us believe this view of creation and our origins is not only the only choice a Christian has, but is also the historic view of the church.

But is this really the case? Is a literal 6-day young-earth reading of creation really the only way to read the text? Indeed, is it even the most historically and Biblically faithful? Many proponents of the Creation movement today would have us believe so. However, when we actually turn to the pages of church history itself, we actually find something quite different. Through a brief study of some of the giants of church history (from antiquity to today) is that a literal creationist reading has not always been the way the church has read the text. I want to briefly consider the works of 6 figures from church history, who I have selected because of their influence as well as their clarity on the subject at hand.

St. Augustine

One of the great giants of the historic Christian faith, St. Augustine, has some very interesting things to say to us in regards to our interpretations of Genesis. In his work On Genesis: A Refutation of the Manichees he deals intently with an explicitly literal interpretation of the opening chapters of Genesis. Carrying on in what could be regarded as an apologetical and polemical tone, he largely proves the impossibility of taking everything in Genesis as literally as possible. He also has quite a strong word towards those who would forsake reason and logic in our observations of the modern world in order to hold on rigidly to such a literal reading. In many ways, this makes Augustine’s comments as relevant today as it did 1600 years ago. Towards the end of his work, he has this to say for such people who hold to rigid readings of Genesis:

There is knowledge to be had, after all, about the earth, about the sky, about the other elements of this world, about the movements and revolutions or even the magnitude and distances of the constellations, about the predictable eclipses of moon and sun, about the cycles of years and seasons, about the natures of animals, fruits, stones and everything else of this kind. And it frequently happens that even non-Christians will have knowledge of this sort in a way that they can substantiate with scientific arguments or experiments. Now it is quite disgraceful and disastrous, something to be on one’s guard against at all costs, that they should ever hear Christians spouting what they claim our Christian literature has to say on these topics, and talking such nonsense that they can scarcely contain their laughter when they see them to be “toto caelo,” as the saying goes, wide of the mark. And what is so vexing is not that misguided people should be laughed at, as that our authors should be assumed by outsiders to have held such views and, to the great detriment of those about whose salvation we are so concerned, should be written off and consigned to the waste paper basket as so many ignoramuses.

Whenever, you see, they catch out some members of the Christian community making mistakes on a subject which they know inside out, and Christians defending their hollow opinions on the authority of our books, on what grounds are they going to trust those books on the resurrection of the dead and the hope of eternal life and the kingdom of heaven, when they suppose they include any number of mistakes and fallacies on matters which they themselves have been able to master either by experiment or by the surest of calculations? It is impossible to say what trouble and grief such rash, self-assured know-alls cause the more cautious and experienced brothers and sisters.[i]

This is a strong word from one of the great church Fathers! What is he getting at? In summary, he is arguing for how dangerous it is for Christians to argue for things from Scripture that simply do not exist, for the sake of their own pride and ignorance. This is so dangerous because, in effect, it is hardening the non-Christians who are experts in the physical observation of this world to the gospel of salvation. What is interesting is how he appears to value the observations of the physical world that come from non-Christians. Augustine does not have a militant view of outside scientific observation, but instead he welcomes it. This comes from Augustine’s confidence in God’s Word and his ability not to force it to say something that it does not say. We would be wise to heed his advice in this area.

Thomas Aquinas

Edward Grant is the Distinguished Professor of History and Philosophy of Science at Indiana University. In his essay Science and Theology in the Middle Ages, he outlines Thomas Aquinas’ view on creation and Biblical interpretation. He quotes Aquinas, who followed in Augustine in his though, as saying the following: “First, the truth of Scripture must be held inviolable. Secondly, when there are different ways of explaining a Scriptural text, no particular explanation should be held so rigidly that, if convincing arguments show it to be false, anyone dare to insist that it still is the definitive sense of the text. Otherwise unbelievers will scorn Sacred Scripture, and the way to faith will be closed to them.”

Grant goes on to explain Aquinas further:

These two vital points constituted the basic medieval guidelines for the application of a continually changing body of scientific theory and observational data to the interpretation of physical phenomena described in the Bible, especially the creation account. The scriptural text must be assumed true. When God “made a firmament, and divided the waters that were under the firmament, from those that were above the firmament,” one could not doubt that waters of some kind must be above the firmament. The nature of that firmament and of the waters above it were, however, inevitably dependent on interpretations that were usually derived from contemporary science. It is here that Augustine and Aquinas cautioned against a rigid adherence to any one interpretation lest it be shown subsequently untenable and thus prove detrimental to the faith.[ii]

What is striking about both Augustine and Aquinas’ view is how they perceive rigid and literal interpretations of Scripture – contrary to scientific evidence – as being so harmful to our evangelism and witness. I wonder if the efforts of outspoken creationists today have similarly hurt our witness in the scientific community today because of their perceived hostility to the efforts of modern science?

John Calvin

Another giant of church history, John Calvin, reveals to us a very similar attitude. During the time of his writing of his commentary on Genesis, it appears that one of the biggest scientific discoveries of his day was that one of the moon’s of Saturn was far superior in size and brightness than that of Earth’s moon. Such a finding seemed to call into question the two lights the God placed into the sky in Genesis 1:16. Writing on this passage, Calvin says this:

Here lies the difference; Moses wrote in a popular style things which, without instruction, all ordinary persons, endued with common sense, are able to understand; but astronomers investigate with great labour whatever the sagacity of the human mind can comprehend. Nevertheless, this study is not to be reprobated, nor this science to be condemned, because some frantic persons are wont boldly to reject whatever is unknown to them. For astronomy is not only pleasant, but also very useful to be known: it cannot be denied that this art unfolds the admirable wisdom of God…Had he (Moses) spoken of things generally unknown, the uneducated might have pleaded excuse that such subjects were beyond their capacity…Moses, therefore, rather adapts his discourse to common usage.[iii]

For Calvin, as we can see, the language of Genesis is in the language of “common usage.” It is no problem for Calvin that science – in this case, astronomy – tells us things that appear to not be in the Bible. There is no discrepancy here. As a matter of fact, the very use of science should lead us to praise. Calvin concludes this passage by saying that those who do not worship God on account of their scientific findings “are convicted by its use of perverse ingratitude unless they acknowledge the beneficence of God.” The true tragedy then is not that science tells us things that the Bible does not, but instead that scientists could gather such great information about the creation that does not lead them to praise its Creator.

B.B. Warfield

Another figure of church history who provides us great insight into an orthodox, historic Biblical interpretation of creation and Genesis is the great Princeton theologian B.B. Warfield. Warfield is often regarded as one of the great champions of Biblical inerrancy and inspiration, yet he referred to himself as an “evolutionist of the purest stripe.” Much of his writing of course was coming during the time when Darwinian Evolution was first exploding on to the scene. In the January 1911 edition of The Princeton Review, Warfield wrote an article called “On the Antiquity and the Unity of the Human Race.” In this article, he wrote: “The question of the antiquity of man has of itself no theological significance. It is to theology, as such, a matter of entire indifference how long man has existed on earth.” [iv] What is of theological significance to Warfield then was that as fallen humans we find our unity in Adam, but as regenerate Christians we find our unity in a new federal head, Jesus Christ. Warfield saw no conflict in this doctrine with that of the age of the earth or the origins of humanity.

Mark Noll, writing for BioLogos, summarizes Warfield’s view of evolutionary theory when he writes, “[Warfield] devoted much effort in his later career to indicating how a conservative view of the Bible could accommodate some, or almost all, of contemporary evolutionary theory.”[v] If a reconciliation between scientific theory and Biblical inspiration and authority was of no issue for a giant like B.B. Warfield, then we should find no trouble ourselves in our attempts at reconciling the two.

Tim Keller

In his fantastic article from the BioLogos website entitled Creation, Evolution and Christian Laypeople, Keller argues for a non-literal and potential evolutionary reading of Genesis 1 and 2. He does so by arguing that these chapters fit into a potential genre called “exalted prose narrative.”[vi] His argument does not stem from trying to fit science into the Bible, but instead comes from “trying to be true to the text, listening as carefully as we can to the meaning of the inspired author.”[vii] What is important for Keller, and he argues should be for us today, is how we view the historicity of Adam. The thrust of his argument is what it means to be “in” a covenantal relationship with someone as our federal head. Those of us who have placed our faith in Christ are united to him as our federal representative. Similarly, those of us who are not in Christ are explained in the Bible to still be “in Adam.” Losing the historicity of Adam begins to have serious problems for our understanding of the Bible (including such passages as Romans 5 and 1 Corinthians 15).

Michael Horton

In his large systematic work The Christian Faith, he argues for an understanding of Genesis 1 and 2 that defies modern creationist movements. Horton understands the creation account as a preamble to a covenant treaty between God and his people. He writes: “The opening chapters of Genesis, therefore, are not intended as an independent account of origins but as the preamble and historical prologue to the treaty between Yahweh and his covenant people. The appropriate response is doxology.”[viii] He goes on to quote the Psalmist who writes:

Know that the Lord, he is God!

It is he who made us, and we are his;

we are his people, and the sheep of his pasture.

Enter his gates with thanksgiving,

and his courts with praise!

Give thanks to him; bless his name! (Psalm 100:3-4)

Horton continues his thoughts on Genesis in the next chapter of his book when he writes:

The point of these two chapters (Genesis 1 and 2) is to establish the historical prologue for God’s covenant with humanity in Adam, leading through the fall and moral chaos of Cain to the godly line of Seth that leads to the patriarchs. If these chapters are not intended as a scientific report, it is just as true that they are not mythological. Rather, they are part of a polemic of “Yahweh versus the Idols” that forms the historical prologue for God’s covenant with Israel. Meredith Kline observes that “these chapters pillage the pagan cosmogonic myth – the slaying of the dragon by the hero-god, followed by celebration of his glory in a royal residence built as a sequel to his victory.” As usual, God is not borrowing from but subversively renarrating the pagan myths, exploiting their symbols for his own revelation of actual historical events.[ix]

Of ultimate importance for Horton then, as it should be for us, is that Yahweh is seen to be Lord over man and creation.

**

My goal in sharing these six examples from the pages of church history is not to influence anyone on a particular reading of Genesis. My goal instead is to show an alternative view of how Christians view Genesis 1 and 2 that is often not shown to us by the loudest voices in the debate or in popular media today. I hope this will allow all of us to see, no matter where we fall in this conversation, that there is great freedom and room for charity in how we interpret and read these passages in the Bible. May our conversations within the church reflect such charity and freedom as we partner together in sharing the gospel and showing the world how science and Christianity are not at all at odds with one another.

[i] Augustine, Works of Saint Augustine, trans. Edmund Hill, vol. 13, On Genesis: On Genesis: a Refutation of the Manichees, Unfinished Literal Commentary On Genesis, the Literal Meaning of Genesis (Hyde Park, NY: New City Press, ©2002), 186-87.

[ii] Lindberg and Numbers, God and Nature. Edward Grant, “Science and Theology in the Middle Ages,” pp. 63-64.

[iii] John Calvin, Calvin’s Commentaries, Volume 1: Genesis (Grand Rapids: Baker), 2005, pp. 86-87 (commentary on Genesis 1:16).

[iv] B.B Warfield, “On the Antiquity and Unity of the Human Race,” The Princeton Theological Review 9 (January 1911): 1.

[v] Mark Noll, “Evangelicals, Creation and Scripture,” BioLogos (November 2009): 9, accessed July 30, 2015, http://biologos.org/uploads/projects/Noll_scholarly_essay.pdf.

[vi] Tim Keller, “Creation, Evolution and Christian Laypeople,” BioLogos (November 2009): 4, accessed July 30, 2015, http://biologos.org/uploads/projects/Keller_white_paper.pdf.

[vii] Ibid., 5

[viii] Michael Scott Horton, The Christian Faith: A Systematic Theology for Pilgrims On the Way (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan, ©2011), pp. 337.

[ix] Ibid., 382.

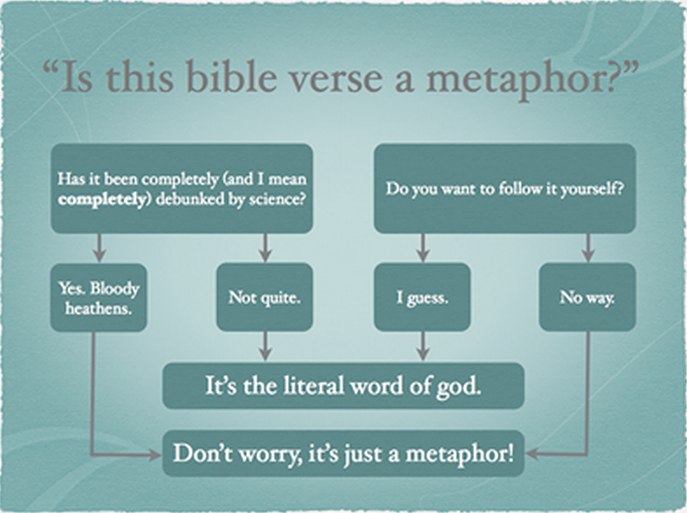

It could be said that one of the great bastions of American Evangelicalism – or perhaps I should say, American Fundamentalism – is the idea of reading the Bible literally. Whether you’re a Christian or not, you’ve probably heard it all before. The Bible is the Word of God, therefore everything it says must be taken “literally” (scare-quotes are intentional). To be fair, I understand where this emphasis on Biblical literalism comes from. Coming off the heels of the Protestant Reformation – which championed the great truth of Sola Scriptura (contrary to popular opinion, this does not mean Protestants affirm Scripture alone, but what is meant instead is that all truth necessary for our salvation and spiritual life is taught either explicitly or implicitly in Scripture) – the Western church was soon met with a new opponent: theological liberalism. At the root of this new religion – and it is a new religion – is the assertion that my own intellect has the right to choose what I want to keep from Scripture and what I want to reject.

In its attempt to hold on to historic Christian orthodoxy, American Evangelicalism – and soon, its fundamentalist counterparts – began to champion Biblical literalism. Biblical literalists will say, “We have no right to pick and choose what we want out of the Bible, after all, it is the Word of God. Therefore, we must read the Bible literally and do everything it says.” I understand where this idea comes from. I do. And I want to be as fair and gracious to its proponents as possible.

The problem is, I strongly disagree with it.

Not a week goes by where I don’t see a Facebook post, a news article, or a comment section with people debating the subject matters of Biblical literalism. Some of the most common arguments against Biblical literalism go something like this:

- Jesus says to serve the poor. A lot of Christians don’t serve the poor, but seem to be interested in telling other people what not to do. If they read their own Bibles, maybe they’d get their act together.

- Why do Christians think they can tell other people what is moral and ethical? Their Bible says that you shouldn’t eat shellfish or wear clothing of mixed fibers – they’re all a bunch of hypocrites.

- Why are they so concerned about marriage and sexual ethics? A bunch of people in the Old Testament were polygamists, so why isn’t that an adequate form of marriage? All Christians do is pick and choose what they like from the Bible.**

I’m sure you’ve read something similar to what I’ve summarized above. Yet, its often not the non-Christians who say the most offensive or dismissive comments in these contexts, its the professed Christians. The most common responses I find from Christians in these situations sound something like this, “Repent or you’re going to hell – the Bible says so”, or “God said it. I believe it. That settles it”, or “Well the Bible says ____ so you’re wrong”, or some other aggressive comment about “what the Bible says.” After all, if the Bible says that men “pisseth against the wall”, then you better be a man and go pee on a wall.

The reality is, we should not be surprised that the culture around us argues based on a position of what the Bible literally says. After all, this concept is what much of the American Church has been championing for the last century. In all fairness, we’ve only brought our cultures Biblical illiteracy on ourselves. By emphasizing one idea – Biblical literalism – we’ve neglected to actually tell people how the Bible is meant to be read and understood. Now its not only the culture around us that doesn’t know how to handle the Bible, but the average lay person sitting in our pews.

The Bible is not a text that is meant to be read literally.

I bet that comment made a lot of you uncomfortable, so I’ll say it again.

The Bible is not a text that is meant to be read literally.

The Bible is a much richer, more robust, far deeper, and more profound book than one that can simply be read literally. No, the Bible is a text that is both living and active (Hebrews 4:12) and is begging to be sought after and understood (2 Timothy 3:16-17). So how then are we meant to read it? How can we properly explain to other Christians and the culture around us how the Bible is meant to be read?

I’m glad you asked. For those of you who know me, I hope you wouldn’t think that I’ve gone off the deep end and rejected the authority of Scripture. For those of you that don’t know me well, I present to you: the bait. Now let me show you the switch.

My proposition for communicating the historic, orthodox and Protestant position on the Bible is fourfold: The Bible is God’s written word that must be read literally within its respective genre and proper redemptive context under the guidance of church tradition.

Sure, the Bible is a text that must be read literally, but not merely literally. It must be read within its respective genre. The Bible is full of various genres that reflect the influence of its author and time period in which it was written. Therefore, we must understand the text within the style that it was written. There are many different genres within the Biblical literature: prose, historical narrative, wisdom literature, poems, apocalyptic literature, and epistles just to name a few. The way we read Old Testament poetry must be different than the way we read New Testament narrative. Metaphors must be read differently than straightforward prose. This is why we don’t read a verse like Psalm 88:7 (“…and you overwhelm me with all your waves”) as literal waves, but as a trial that comes from God himself. When we read John 1:43 (“The next day Jesus decided to go to Galilee”), we understand what it meant. Jesus went to Galilee.

In a similar way, we must understand the Bible in its redemptive context. Where does the passage in question fall in God’s story of human redemption? After all, if the entirety of the Scriptures are meant to illuminate Christ for us (Luke 24:27, Acts 17:11-12), then the most important task of our Biblical studies is to seek Christ. This gives us the ability understand what it means for the writer of Hebrews to say, “Long ago, at many times and in many ways, God spoke to our fathers by the prophets, but in these last days he has spoken to us by his Son (Hebrews 1:1-2).” If you need help with this, I wrote a helpful post to get you started here.

As for reading the Bible under the guidance of church tradition, this gets us into muddy water that doesn’t fall under the intention of this post. One of the most basic differences between Roman and Protestant theology is the role of tradition in the life of the church. While Protestants affirm Sola Scriptura (defined above), we do not discount the importance of church tradition. It is a lens by which we can come to better understand God’s Word in the life of his people. We have the benefit of standing on 2000 years of men and women who have gone before us in faith, and we should not ignore what the Holy Spirit has faithfully taught our ancestors.

C.S. Lewis – in one of his snarkier moments – has a great explanation of what happens when we reduce the Bible to mere Biblical literalism: “There is no need to be worried by facetious people who try to make the Christian hope of ‘Heaven’ ridiculous by saying they do not want to ‘spend eternity playing harps’. The answer to such people is that if they cannot understand books written for grown-ups, they should not talk about them.” In other words, if you treat everything in the Bible simply as being literal, then you are unable to adequately understand it. This is why we must have a much more “grown-up” understanding of our Bibles. My proposal is to abandon the solitary tower of Biblical literalism and instead expand our territory to a much healthier and more faithful understanding. We must read and explain the Bible as God’s written word that must be read literally within its respective genre and proper redemptive context under the guidance of church tradition. When we do, we’ll not only better understand the Bible ourselves, but we’ll have better explanations for the society around us, we’ll be better equipped to approach the big issues of our day (ethics, science), and most importantly we’ll be more faithful to the God who was pleased to reveal his Word to us.

—–

**Note the irony here. Biblical literalism really took shape against a backdrop of theological liberalism, which argued that we have the ability to pick and choose from the Bible. Now that fundamentalists and evangelicals have championed literalism for so long – without any understanding of the historic, orthodox way of reading Scripture – the tables have now been flipped on us. The culture around us reads the Bible literally, and we’re the ones left being accused of cherry picking. Funny how that works, yeah?

My wife and I are currently in the process of finishing up our 2014 taxes. Like the rest of you, we’re busy trying to figure out whether we have all of our tax documents, if we’ve entered all of the information correctly, and if we’ve maximized the greatest possible return on our taxes. Now, I don’t know much about taxes or how they’re calculated. I’ve always just entered the standard information on my W-4 and sort of…hoped for the best around tax season. What I do know is, if I’ve paid more then I’ve supposed to during the year – I get something back. If I were to somehow pay the exact right amount, I wouldn’t get anything back – but I also wouldn’t owe anything. Sadly, I’ve been in the position before where I didn’t pay enough during the year and I end up owing money to the government. Nobody likes that. To be honest, my knowledge about taxes comes down to nothing more than a gamble – I never really know what my return is going to be once everything gets filed.

I’ve talked to a lot of people who – in a similar yet much more significant way – take a gamble on God. Many people have a position towards God – if He exists, anyways – that just trying hard enough to be a good person puts them on right terms with God. You might think, “If I do enough good things, wouldn’t God owe me?” Or, at the very least, “If my good and bad deeds even out, God and I will be neutral, right?” You might even think that it’s only if your bad deeds severely outweigh your good that God would have any business punishing you. Do your best, make people happy, and God owes me one.

Is that right? Or are you taking a gamble?

When we think about God, ourselves, and our relationship to him, we need to think about these things on his terms, not on our terms. Anything less is wishful thinking. So here’s the thing about our good deeds. We tend to think of all of our good accomplishments – whether it is serving a homeless person or smiling to our neighbor – as going above and beyond. We like to think that our good actions are a positive investment that will net us a big return. But the reality is, being perfectly good and obedient is just the baseline of what is expected of us. There is no going above and beyond where good deeds are concerned. The Apostle Paul explains this at length in the Book of Romans when he says, “Now to the one who works, his wages are not counted as a gift but as his due” (Romans 4:7). You owe God perfect obedience and good works, nothing you do is above and beyond the expectations.

But here’s the problem. None of us have ever or could ever say that we’ve had perfect obedience and good work. You might say, “I’m not as bad as ____ (fill that in with whatever your movable standard is),” but that doesn’t mean anything to a perfectly just God. Either you’ve perfectly obeyed, or you haven’t. As hard as it may be to admit, in our heart of hearts we all know that we haven’t been able to do this (Romans 3:23). Even if we could perfectly obey from this moment forward, we would still have a blemished track record that we couldn’t make up for. No matter how hard we try to be a good person, we’ll never be able to pay enough back to God.

You might be saying to yourself, “That sounds ridiculous. Of course nobody can be perfect all the time, how could God punish someone who is relatively good?” The problem with that question is that its relative. Again, if we think in God’s terms and not our own, then we need to be prepared to say that things cannot be relative. Either God is just and punishes sin, or he is the cosmic absent deity who cares very little about your life.

So where do we go from here? Let’s consider again what Paul has to say in the next verse of Romans, “And to the one who does not work but believes in him who justifies the ungodly, his faith is counted as righteousness” (Romans 4:8). What is Paul saying here? Is Paul saying that we don’t need to try to do good at all as long as we believe in something? No, in fact, elsewhere Paul will passionately explain how those who believe must necessarily work as hard as possible to love God and love their neighbor.

What the Apostle Paul is explaining in these two verses is that our forgiveness, our right standing with God, cannot come from what we do. That is impossible, because we can’t do enough to earn that. Our forgiveness and our right standing, must come simply through faith in the one who freely gives that to us. And who is that? Paul explains:

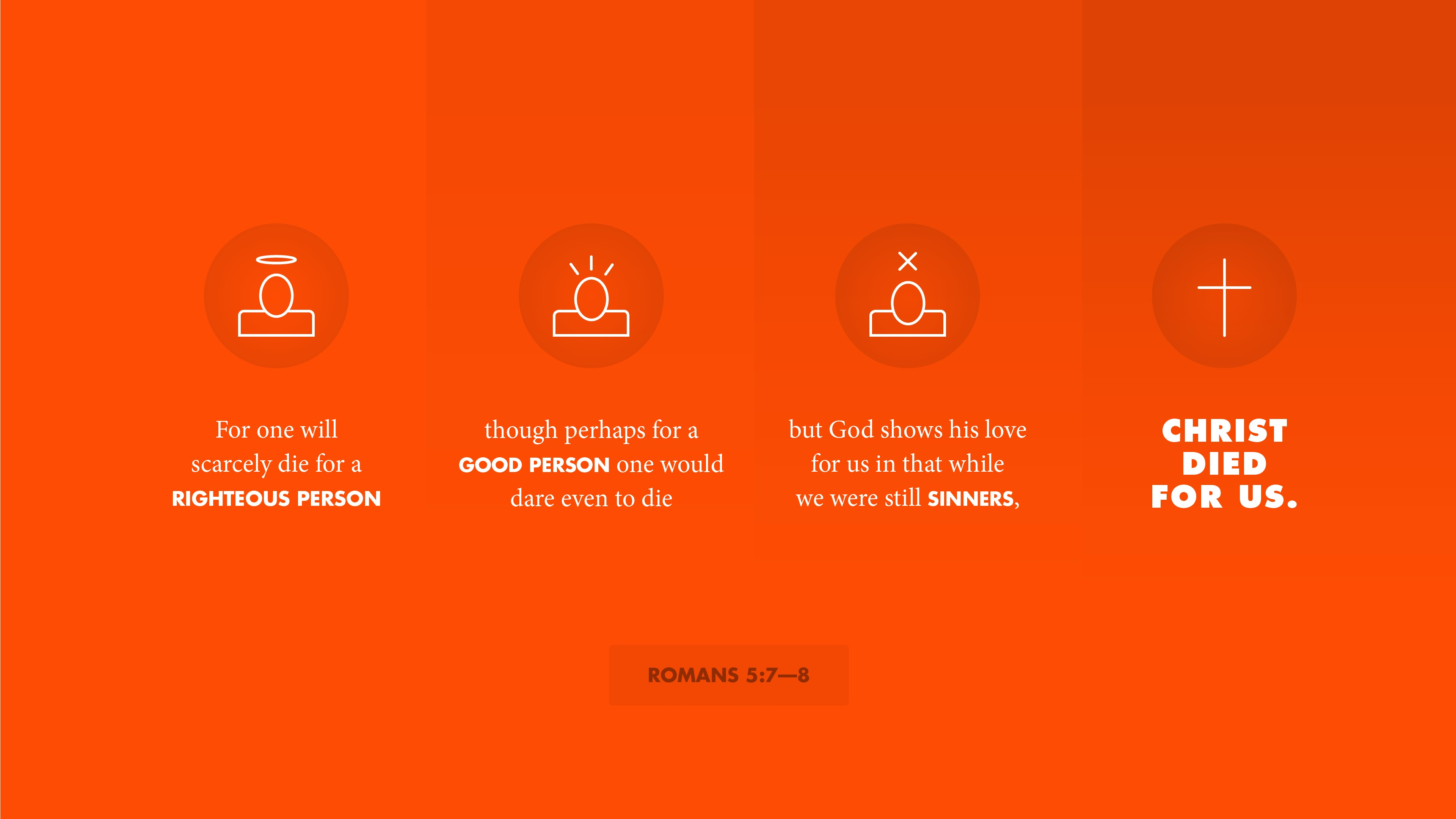

For while we were still weak, at the right time Christ died for the ungodly. For one will scarcely die for a righteous person—though perhaps for a good person one would dare even to die—but God shows his love for us in that while we were still sinners, Christ died for us. Since, therefore, we have now been justified by his blood, much more shall we be saved by him from the wrath of God (Romans 5:6–9).

See, God is not only just but he is also gracious, merciful, and abounding in steadfast love and patience. Yet, every single one of us must face the reality that when we stand before God and hand in all of our documents, we each will owe far more than we will be able to pay. But for the one who comes empty handed, not boasting in his success and earnings, but pleading only the blood of Christ, he can and will be forgiven. His return will not be what he is due, but what is due to Christ – the full inheritance and manifold blessings that are worthy of a son or daughter of God.

So friend, let me ask you: are you taking a gamble with God? Are you banking on your own insufficient merit and knowledge in hopes that you’ve made enough positive investment to get a big return? Acknowledge your inadequacy and ask for the grace and mercy from the one who gives it abundantly, and receive a return worth far more than can be measured: love, acceptance, forgiveness, mercy, kindness, adoption, peace.