How are we today as the Church meant to read the creation account as told in Genesis 1 and 2? Many Evangelical leaders today paint the picture that the only faithful interpretations of these chapters are an explicitly “literal” one, meaning that Christians must believe in a young earth, creationist science, etc. One only needs to briefly read and listen to the likes of Ken Ham and Ray Comfort to see how their teachings have permeated into many modern churches and pastors. Such leaders would have us believe this view of creation and our origins is not only the only choice a Christian has, but is also the historic view of the church.

But is this really the case? Is a literal 6-day young-earth reading of creation really the only way to read the text? Indeed, is it even the most historically and Biblically faithful? Many proponents of the Creation movement today would have us believe so. However, when we actually turn to the pages of church history itself, we actually find something quite different. Through a brief study of some of the giants of church history (from antiquity to today) is that a literal creationist reading has not always been the way the church has read the text. I want to briefly consider the works of 6 figures from church history, who I have selected because of their influence as well as their clarity on the subject at hand.

St. Augustine

One of the great giants of the historic Christian faith, St. Augustine, has some very interesting things to say to us in regards to our interpretations of Genesis. In his work On Genesis: A Refutation of the Manichees he deals intently with an explicitly literal interpretation of the opening chapters of Genesis. Carrying on in what could be regarded as an apologetical and polemical tone, he largely proves the impossibility of taking everything in Genesis as literally as possible. He also has quite a strong word towards those who would forsake reason and logic in our observations of the modern world in order to hold on rigidly to such a literal reading. In many ways, this makes Augustine’s comments as relevant today as it did 1600 years ago. Towards the end of his work, he has this to say for such people who hold to rigid readings of Genesis:

There is knowledge to be had, after all, about the earth, about the sky, about the other elements of this world, about the movements and revolutions or even the magnitude and distances of the constellations, about the predictable eclipses of moon and sun, about the cycles of years and seasons, about the natures of animals, fruits, stones and everything else of this kind. And it frequently happens that even non-Christians will have knowledge of this sort in a way that they can substantiate with scientific arguments or experiments. Now it is quite disgraceful and disastrous, something to be on one’s guard against at all costs, that they should ever hear Christians spouting what they claim our Christian literature has to say on these topics, and talking such nonsense that they can scarcely contain their laughter when they see them to be “toto caelo,” as the saying goes, wide of the mark. And what is so vexing is not that misguided people should be laughed at, as that our authors should be assumed by outsiders to have held such views and, to the great detriment of those about whose salvation we are so concerned, should be written off and consigned to the waste paper basket as so many ignoramuses.

Whenever, you see, they catch out some members of the Christian community making mistakes on a subject which they know inside out, and Christians defending their hollow opinions on the authority of our books, on what grounds are they going to trust those books on the resurrection of the dead and the hope of eternal life and the kingdom of heaven, when they suppose they include any number of mistakes and fallacies on matters which they themselves have been able to master either by experiment or by the surest of calculations? It is impossible to say what trouble and grief such rash, self-assured know-alls cause the more cautious and experienced brothers and sisters.[i]

This is a strong word from one of the great church Fathers! What is he getting at? In summary, he is arguing for how dangerous it is for Christians to argue for things from Scripture that simply do not exist, for the sake of their own pride and ignorance. This is so dangerous because, in effect, it is hardening the non-Christians who are experts in the physical observation of this world to the gospel of salvation. What is interesting is how he appears to value the observations of the physical world that come from non-Christians. Augustine does not have a militant view of outside scientific observation, but instead he welcomes it. This comes from Augustine’s confidence in God’s Word and his ability not to force it to say something that it does not say. We would be wise to heed his advice in this area.

Thomas Aquinas

Edward Grant is the Distinguished Professor of History and Philosophy of Science at Indiana University. In his essay Science and Theology in the Middle Ages, he outlines Thomas Aquinas’ view on creation and Biblical interpretation. He quotes Aquinas, who followed in Augustine in his though, as saying the following: “First, the truth of Scripture must be held inviolable. Secondly, when there are different ways of explaining a Scriptural text, no particular explanation should be held so rigidly that, if convincing arguments show it to be false, anyone dare to insist that it still is the definitive sense of the text. Otherwise unbelievers will scorn Sacred Scripture, and the way to faith will be closed to them.”

Grant goes on to explain Aquinas further:

These two vital points constituted the basic medieval guidelines for the application of a continually changing body of scientific theory and observational data to the interpretation of physical phenomena described in the Bible, especially the creation account. The scriptural text must be assumed true. When God “made a firmament, and divided the waters that were under the firmament, from those that were above the firmament,” one could not doubt that waters of some kind must be above the firmament. The nature of that firmament and of the waters above it were, however, inevitably dependent on interpretations that were usually derived from contemporary science. It is here that Augustine and Aquinas cautioned against a rigid adherence to any one interpretation lest it be shown subsequently untenable and thus prove detrimental to the faith.[ii]

What is striking about both Augustine and Aquinas’ view is how they perceive rigid and literal interpretations of Scripture – contrary to scientific evidence – as being so harmful to our evangelism and witness. I wonder if the efforts of outspoken creationists today have similarly hurt our witness in the scientific community today because of their perceived hostility to the efforts of modern science?

John Calvin

Another giant of church history, John Calvin, reveals to us a very similar attitude. During the time of his writing of his commentary on Genesis, it appears that one of the biggest scientific discoveries of his day was that one of the moon’s of Saturn was far superior in size and brightness than that of Earth’s moon. Such a finding seemed to call into question the two lights the God placed into the sky in Genesis 1:16. Writing on this passage, Calvin says this:

Here lies the difference; Moses wrote in a popular style things which, without instruction, all ordinary persons, endued with common sense, are able to understand; but astronomers investigate with great labour whatever the sagacity of the human mind can comprehend. Nevertheless, this study is not to be reprobated, nor this science to be condemned, because some frantic persons are wont boldly to reject whatever is unknown to them. For astronomy is not only pleasant, but also very useful to be known: it cannot be denied that this art unfolds the admirable wisdom of God…Had he (Moses) spoken of things generally unknown, the uneducated might have pleaded excuse that such subjects were beyond their capacity…Moses, therefore, rather adapts his discourse to common usage.[iii]

For Calvin, as we can see, the language of Genesis is in the language of “common usage.” It is no problem for Calvin that science – in this case, astronomy – tells us things that appear to not be in the Bible. There is no discrepancy here. As a matter of fact, the very use of science should lead us to praise. Calvin concludes this passage by saying that those who do not worship God on account of their scientific findings “are convicted by its use of perverse ingratitude unless they acknowledge the beneficence of God.” The true tragedy then is not that science tells us things that the Bible does not, but instead that scientists could gather such great information about the creation that does not lead them to praise its Creator.

B.B. Warfield

Another figure of church history who provides us great insight into an orthodox, historic Biblical interpretation of creation and Genesis is the great Princeton theologian B.B. Warfield. Warfield is often regarded as one of the great champions of Biblical inerrancy and inspiration, yet he referred to himself as an “evolutionist of the purest stripe.” Much of his writing of course was coming during the time when Darwinian Evolution was first exploding on to the scene. In the January 1911 edition of The Princeton Review, Warfield wrote an article called “On the Antiquity and the Unity of the Human Race.” In this article, he wrote: “The question of the antiquity of man has of itself no theological significance. It is to theology, as such, a matter of entire indifference how long man has existed on earth.” [iv] What is of theological significance to Warfield then was that as fallen humans we find our unity in Adam, but as regenerate Christians we find our unity in a new federal head, Jesus Christ. Warfield saw no conflict in this doctrine with that of the age of the earth or the origins of humanity.

Mark Noll, writing for BioLogos, summarizes Warfield’s view of evolutionary theory when he writes, “[Warfield] devoted much effort in his later career to indicating how a conservative view of the Bible could accommodate some, or almost all, of contemporary evolutionary theory.”[v] If a reconciliation between scientific theory and Biblical inspiration and authority was of no issue for a giant like B.B. Warfield, then we should find no trouble ourselves in our attempts at reconciling the two.

Tim Keller

In his fantastic article from the BioLogos website entitled Creation, Evolution and Christian Laypeople, Keller argues for a non-literal and potential evolutionary reading of Genesis 1 and 2. He does so by arguing that these chapters fit into a potential genre called “exalted prose narrative.”[vi] His argument does not stem from trying to fit science into the Bible, but instead comes from “trying to be true to the text, listening as carefully as we can to the meaning of the inspired author.”[vii] What is important for Keller, and he argues should be for us today, is how we view the historicity of Adam. The thrust of his argument is what it means to be “in” a covenantal relationship with someone as our federal head. Those of us who have placed our faith in Christ are united to him as our federal representative. Similarly, those of us who are not in Christ are explained in the Bible to still be “in Adam.” Losing the historicity of Adam begins to have serious problems for our understanding of the Bible (including such passages as Romans 5 and 1 Corinthians 15).

Michael Horton

In his large systematic work The Christian Faith, he argues for an understanding of Genesis 1 and 2 that defies modern creationist movements. Horton understands the creation account as a preamble to a covenant treaty between God and his people. He writes: “The opening chapters of Genesis, therefore, are not intended as an independent account of origins but as the preamble and historical prologue to the treaty between Yahweh and his covenant people. The appropriate response is doxology.”[viii] He goes on to quote the Psalmist who writes:

Know that the Lord, he is God!

It is he who made us, and we are his;

we are his people, and the sheep of his pasture.

Enter his gates with thanksgiving,

and his courts with praise!

Give thanks to him; bless his name! (Psalm 100:3-4)

Horton continues his thoughts on Genesis in the next chapter of his book when he writes:

The point of these two chapters (Genesis 1 and 2) is to establish the historical prologue for God’s covenant with humanity in Adam, leading through the fall and moral chaos of Cain to the godly line of Seth that leads to the patriarchs. If these chapters are not intended as a scientific report, it is just as true that they are not mythological. Rather, they are part of a polemic of “Yahweh versus the Idols” that forms the historical prologue for God’s covenant with Israel. Meredith Kline observes that “these chapters pillage the pagan cosmogonic myth – the slaying of the dragon by the hero-god, followed by celebration of his glory in a royal residence built as a sequel to his victory.” As usual, God is not borrowing from but subversively renarrating the pagan myths, exploiting their symbols for his own revelation of actual historical events.[ix]

Of ultimate importance for Horton then, as it should be for us, is that Yahweh is seen to be Lord over man and creation.

**

My goal in sharing these six examples from the pages of church history is not to influence anyone on a particular reading of Genesis. My goal instead is to show an alternative view of how Christians view Genesis 1 and 2 that is often not shown to us by the loudest voices in the debate or in popular media today. I hope this will allow all of us to see, no matter where we fall in this conversation, that there is great freedom and room for charity in how we interpret and read these passages in the Bible. May our conversations within the church reflect such charity and freedom as we partner together in sharing the gospel and showing the world how science and Christianity are not at all at odds with one another.

[i] Augustine, Works of Saint Augustine, trans. Edmund Hill, vol. 13, On Genesis: On Genesis: a Refutation of the Manichees, Unfinished Literal Commentary On Genesis, the Literal Meaning of Genesis (Hyde Park, NY: New City Press, ©2002), 186-87.

[ii] Lindberg and Numbers, God and Nature. Edward Grant, “Science and Theology in the Middle Ages,” pp. 63-64.

[iii] John Calvin, Calvin’s Commentaries, Volume 1: Genesis (Grand Rapids: Baker), 2005, pp. 86-87 (commentary on Genesis 1:16).

[iv] B.B Warfield, “On the Antiquity and Unity of the Human Race,” The Princeton Theological Review 9 (January 1911): 1.

[v] Mark Noll, “Evangelicals, Creation and Scripture,” BioLogos (November 2009): 9, accessed July 30, 2015, http://biologos.org/uploads/projects/Noll_scholarly_essay.pdf.

[vi] Tim Keller, “Creation, Evolution and Christian Laypeople,” BioLogos (November 2009): 4, accessed July 30, 2015, http://biologos.org/uploads/projects/Keller_white_paper.pdf.

[vii] Ibid., 5

[viii] Michael Scott Horton, The Christian Faith: A Systematic Theology for Pilgrims On the Way (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan, ©2011), pp. 337.

[ix] Ibid., 382.

The weight of this topic requires a lengthy blog post. I recognize that this is much longer than most people care to read on a blog site, so for convenience I have provided 5 break points in the article that you can click on and come back and read at any time:

We Are Asking the Wrong Question

Why is There Pain and Evil in the World?

So How Should Christians Respond?

—–

It is likely that since the beginning of time, every civilization has dealt with the same issue. Certainly since the beginning of written history, each succeeding generation resurrects one big question: Why is there pain and evil in the world? The question can take many forms; these variations almost always add God into the mix, something to the effect of “If God is all-good, and God is all-powerful, why does evil exist?”

In a post-modern era of no absolutes, attempts to respond to the “big questions” are now nothing but over-clichéd attempts to make people feel better about themselves. The Church should be a beacon of truth and light that provides a unique and Christian answer to the question.

Unfortunately, this isn’t the case.

We have lost our way. The Church has blended worldly desires for cheap and quick solutions with a slight spiritual blend to offer nothing more than a sugar-coated shell that is hollow on the inside. We have fallen so far that we now answer the “Problem of Pain” with answers such as:

- “God just needed another angel in heaven” (Christianity does not teach that we become angels after death, so I have no idea why we allow this idea to fester).

- “Evil is just the absence of God” (so God is no longer big enough to be all-present?)

- “This [insert natural disaster, economic collapse, war] is God’s punishment on [insert people group] for doing [insert sin]” (OK, but seriously, when did everyone become a prophet? And show me a Biblical precedent for natural disasters being a routine punishment from God).

- “You didn’t have enough faith for good things to happen” (Riiiiight).

- “It is only pain and suffering in our eyes. You just need to change your perspective” (So is there no such thing as absolute evil or absolute good?)

- “God isn’t really ‘sovereign’, that is why we have free will to do what we want” (If you don’t believe in a god who can usurp man’s free will, you don’t believe in a god at all).

These are trite answers and only serve to undermine the riches of Christian faith.

I have a problem with this so-called “Problem of Pain.”

So What Is the Problem?

The real issue being discussed is the existence of pain, evil and suffering in the world. We like the idea of a good and loving god, but often it is hard to reconcile that idea with everything we see in the world around us. What about all of the wars, people dying of starvation and natural disasters, sex trafficking, cancer, murder, disease? Why do bad things happen to good people? What about death?

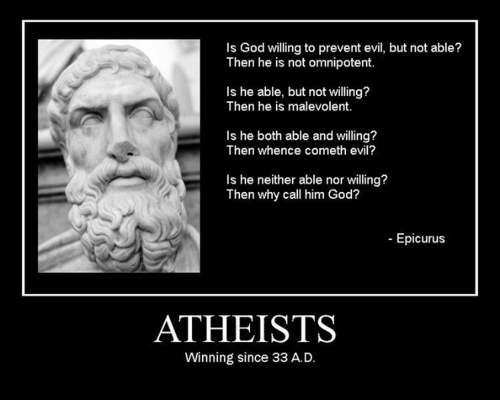

The philosopher first credited with ‘debunking’ God because of the existence of evil, pain and suffering was a man named Epicurus (341-270 BC). A Greek philosopher by trade, Epicurus narrowed down the problem of reconciling evil with God in a simple argument, called the Epicurean Paradox:

Is God willing to prevent evil, but not able? Then he is not omnipotent.

Is he able, but not willing?Then he is malevolent.

Is he both able and willing? Then whence cometh evil?

Is he neither able nor willing? Then why call him God?

The Epicurean Paradox could also be narrowed down into three easy steps, which I will refer to for the remainder of this article:

- God is all-powerful (omnipotent).

- God is all-good.

- Evil exists.

Because of point three, Epicurus would say, God is either not all-powerful or he is not all-good. This shouldn’t be an unfamiliar concept to anyone. Surely everyone has experienced some sort of pain, suffering, or evil that causes them to say “How could a good God exist?”

Let us try to address these questions: How could a loving God allow bad things to happen to good people? How could a good God allow evil to exist?

We Are Asking the Wrong Question

I am going to make the argument that the above questions are invalid, and here’s why:

There’s no such thing as a good person.

That’s right. None of us, no one, not one, is good. Jesus himself said, “…No one is good except God alone” (Luke 18:19b).

The Bible teaches that we are all inherently born with a sin nature. We all have a bend towards sin from the day we are come out of the womb. It is because of this sin nature that we are tainted and corrupt. The book of Romans has a lot to say about the existence of evil. Look at what its author Paul has to say:

None is righteous, no, not one;

no one understands;

no one seeks for God.

All have turned aside; together they have become worthless;

no one does good,

not even one.”

“Their throat is an open grave;

they use their tongues to deceive.”

“The venom of asps is under their lips.”

“Their mouth is full of curses and bitterness.”

“Their feet are swift to shed blood;

in their paths are ruin and misery,

and the way of peace they have not known.”

“There is no fear of God before their eyes.”

You might be reading this while saying to yourself, “This guy is off his rocker! He’s assuming I’m going to believe what the Bible says.” I’m not, because you already know in your heart that what this passage says is true.

Still fighting it? Then ask yourself the following questions: Who taught you how to lie? Who taught you how to covet something that wasn’t yours? Who taught you how to get angry and throw temper tantrums as a child? No one did. Those desires and sinful bends were in you since you were born.

All of this is to say that when we ask the question “Why does God allow bad things to happen to good people?” we are asking the wrong question. It is a man-centered question which doesn’t put God first. This question must be asked in a theocentric (God-centered) manner, not an anthropocentric (man-centered) manner. Author and philosopher CS Lewis said it best when he said:

The problem of reconciling human suffering with the existence of a God who loves, is only insoluble so long as we attach a trivial meaning to the word ‘love’, and look on things as if man were the centre of them. Man is not the centre. God does not exist for the sake of man. Man does not exist for his own sake. “Thou hast created all things, and for they pleasure they are and were created.” We were made not primarily that we may love God (though we were made for that too) but that God may love us, that we may become objects in which the Divine love may rest ‘well pleased’.

So why does God allow bad things to happen to good people? He doesn’t, because there are no good people. Let’s take a look at the second question to get a better understanding of why evil, pain and death exists in the first place.

Why is There Pain and Evil in the World?

As for the latter question, why does God allow evil to exist? Simply put, because we do not exist in a vacuum. Were God to simply eradicate evil, we would not exist. Evil cannot go unpunished, and as Scripture puts it, “The wages of sin is death” (Romans 6:23). This isn’t just a physical death. This is the death of all things that are good and right. The world is no longer the way it was supposed to be. Why does evil continue to exist? Because we have chosen it. As contributors in the human race we have all chosen to go our own way, to turn from God, and to give in to our own desires. Our anger, lust and pride mixes and stirs into one giant blue and green sphere of hostility, hatred and death floating in space.

Here’s the kicker: we’re all guilty. Every single one of us has contributed to the evil, pain and suffering that exists in the world. We have at one time wounded, ignored, and hurt others in ways they’ll never forget. We all lust after and covet things that we shouldn’t have, which causes us to chase after all of the wrong things. No one is exempt from the curse of sin and death – “for all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God” (Romans 3:23). All. Not some. All. Me, you, everyone.

Why does evil exist? Because we’re sinners.

So How Should Christians Respond?

With the above foundations fueling our understanding of the questions at hand, I further suggest that in reality there is no “Problem of Evil” at all. The Epicurean Paradox is a paradox itself, because there is no paradox. Properly understood, a good, loving and all-powerful God is perfectly reconcilable with the existence of pain and evil.

And this is why I have a problem, a bone to pick if you will. So many Church members today are completely misinformed, to the point that we don’t even understand that the answer is sitting right in front of us.

The Christian faith does not teach that you need to believe good things can happen in order for them to happen, that we become angels after death, or that God is unable to prevent evil. The Christian faith does not teach that God is malevolent, likes to watch us suffer, or is generally uninvolved with our lives.

On the contrary, the Christian faith teaches that God is SO good, SO loving, that he can bring the best good from the worst evil. As the early church thinker St. Augustine said,

Since God is the highest good, He would not allow any evil to exist in His works, unless His omnipotence and goodness were such as to bring good even out of evil.

There are examples of this all over the Bible. God is a redemptive God, and we consistently see him turning evil into good in the lives of people like Joseph, David and Paul. But what better place to see this take place than on the work of Christ on the cross! It is with the death and subsequent resurrection of Christ that we see the ultimate example of good coming out of evil. What the world intended to use to destroy God, God intended to use to purchase salvation for all of those who would believe in him for life. How can one conceive of a higher good than that!? As condemned sinners, who brought evil and death upon ourselves, God still looked upon us and said “This will not do!”

For while we were still weak, at the right time Christ died for the ungodly. For one will scarcely die for a righteous person—though perhaps for a good person one would dare even to die— but God shows his love for us in that while we were still sinners, Christ died for us. -Romans 5:6-8

This is the essence of the Christian faith. This is the gospel. This so-called “Problem of Evil” is completely squashed in the work of Jesus on the cross. What amazing, undeserved grace!

Summary

Properly understood, there is no “Problem of Evil.” The questions we often use to asses this so-called problem are the wrong questions because they focused on men rather than God. We presuppose that we deserve good things to happen to us, when really we all deserve death.

We began by looking at the Epicurean Paradox, which we summarized as follows:

- God is all-powerful (omnipotent).

- God is all-good.

- Evil exists.

When we stop at point 3, our first inclination is to think that point 3 would contradict point 1 or 2. However, point 3 is not the end of the story. As author and apologist Dr. Greg Bahnsen points out, we must continue on to a point 4:

4. God has a morally sufficient reason for the evil which exists.

Christianity teaches that God is so immensely good, so far beyond our comprehension, that He can produce good from even the worst and most tragic of evils. Now, let me be clear; this isn’t to say that we are always going to know the exact reason for individual circumstances of pain and evil. We can’t always know why someone has cancer, or why our friends would be killed, or why terrorists would kill hundreds of people. We can’t always know why we’d lose our job, or someone would choose to cause us immense pain and hurt.

But we can be sure of two things.

The first is that the consequence of our sin is death and suffering. All of us have sinned, and we have all contributed to the pain and hurt we see in the world. What is the meaning of all of this death and suffering in the world? The consequences of sin are outrageous.

Second, we have an amazing, sacrificial and loving Savior. We have a God who does not desire us to eternally face the consequence of our sin, but wants to reconcile us and redeem us, allowing us to experience the grace and mercy that only the perfect Creator can give. We can have confidence that even though we have trouble in this life, Jesus has overcome the world.

I know there will be plenty of non-Christians who read this. And I know every one of you have gone or are currently going through some kind of hurt and some kind of pain that causes you to be angry and bitter with the idea of a loving and all-powerful God. Come, taste and see. The Lord is good. I invite you to send me a message. Let’s talk about it. There is hope, there are answers, and they’re found in Jesus.

Christians, we have a better answer than what the world can provide. It just is. When you feel hurt or pain, when you see evil in the world, cling to the cross. Rejoice in our Savior. And then go help someone else who can’t reconcile pain and evil with the idea of a loving God. We have the answer for reconciling pain and evil, for bringing hope to a dark world, and for restoring hurting people with a loving God. Don’t give in to cheap, worldly answers.

The gospel changes everything.